Exploring historic Fort Selkirk, Yukon

Fort Selkirk is a remote ghost town, one of the oldest communities in the Yukon, and a gem of a historic site that few people will ever see. The only way to reach it is by boat, but each year on Parks Day, free boat shuttles are offered. Canada’s Parks Day is celebrated on the third Saturday of July each year – this year, it was on the 20th, and I reserved spots for myself, Cathy and my niece, Bobbie, several weeks early.

My last visit to Fort Selkirk was in August 1997, when my son Steven and I spent 11 days canoeing from Whitehorse to Dawson City. My journal about Fort Selkirk from that trip begins with:

Fort Selkirk – what can I say about this magic place in 2 or 3 paragraphs? … We spent 21 hours there, and took almost 100 photographs of the 34 buildings and 2 cemeteries – apart from the work crew and support people, the village was ours. On the previous day, dozens of people had arrived, stretching the capacity of the campground to the limit. While we were there, several people paddled by without stopping – while I don’t understand why they did it, they have my thanks!

You can read about that entire trip in my article, “Our Time Machine is a Canoe“.

The shuttle boats run from a launch site near the Pelly Farm, on the Pelly River near its confluence with the Yukon River. It’s a long haul from Whitehorse – we left the house at 07:30, and made a quick stop at Fox Lake to pick up Bobbie, who was camping there with friends. The mandatory stop at Braeburn Lodge was made to pick up a few of Steve’s massive cinnamon buns – you can’t head off into the wilderness without appropriate survival rations!

We turned off the North Klondike Highway at about 10:50. To get to the Pelly River road, you go through a residential part of Pelly Crossing. The route is rather confusing, but there were signs to keep us on the right road.

The Pelly River is very impressive, and the broad glacier-carved valley it flows through is lovely.

Sally Robinson at Historic Sites had told me that it was an hour from the highway to the boat launch, and that there was a sign at the half-way point to confirm that you’re on the right road 🙂

There’s nothing fancy about the road – here, it crosses Caribou Creek.

Our first look at historic Pelly Farm (a.k.a. Pelly River Ranch Farm since 1954 when the Bradley family bought it). The sign on the tree says “You Made It”, with a wonderful caricature of a grazing cow.

We reached the boat launch right at noon. There were more vehicles there than I had expected. I don’t know how many people had been allowed to register, but heard that there was a long waiting list of people who wanted to go.

Both shuttle boats left as we arrived, and we had a 35-minute wait for one of them to return.

A couple of excellent publications about Fort Selkirk were available, so we did some reading while waiting for the boat. These publications are available online for free as pdfs: Fort Selkirk (walking tour); and A Look Back in Time: The Archaeology of Fort Selkirk.

At 12:40 we got a glimpse of Pelly Farm. Tours were being offered and we hoped to be able to take one in the afternoon.

I was surprised to see an enormous amount of recent erosion damage along the Pelly.

Unless you were really paying attention, you wouldn’t notice entering the main Yukon River flow, as it has very much the same size and character as the Pelly. A few minutes after entering the Yukon River, though, we got our first look at Fort Selkirk, at 12:53 pm. I hoped that everyone else was as excited by the sight as I was.

A Historic Sites interpreter gave us a brief orientation to the site, offered booklets to anyone who didn’t have them yet, and then we were off on our exploration.

There were still a few campers in the large campsite, but most if not all canoeists had already resumed their trip to Dawson City. The interpreter had told us that most of the 1,200 to 1,500 annual visitors Fort Selkirk arrive by canoe.

When the Yukon River was the primary highway in the Yukon, Fort Selkirk was a busy place. This photo was shot by Whitehorse professional photographer Ephraim J. Hamacher in 1903. When the North Klondike Highway opened in 1950, though, traffic on the river died, and Fort Selkirk was abandoned soon after.

Charlie Stone, the government telegraph operator, began building this house for his mother in 1935, but she died before it was completed. This was the most modern house in Fort Selkirk, and the only one with indoor plumbing.

This small and simple cabin appears to have been built in the early 1920s, possibly by Neville Armstrong, a gold miner at Russell Creek on the Macmillan River and a big game outfitter.

This is the interior of the cabin above.

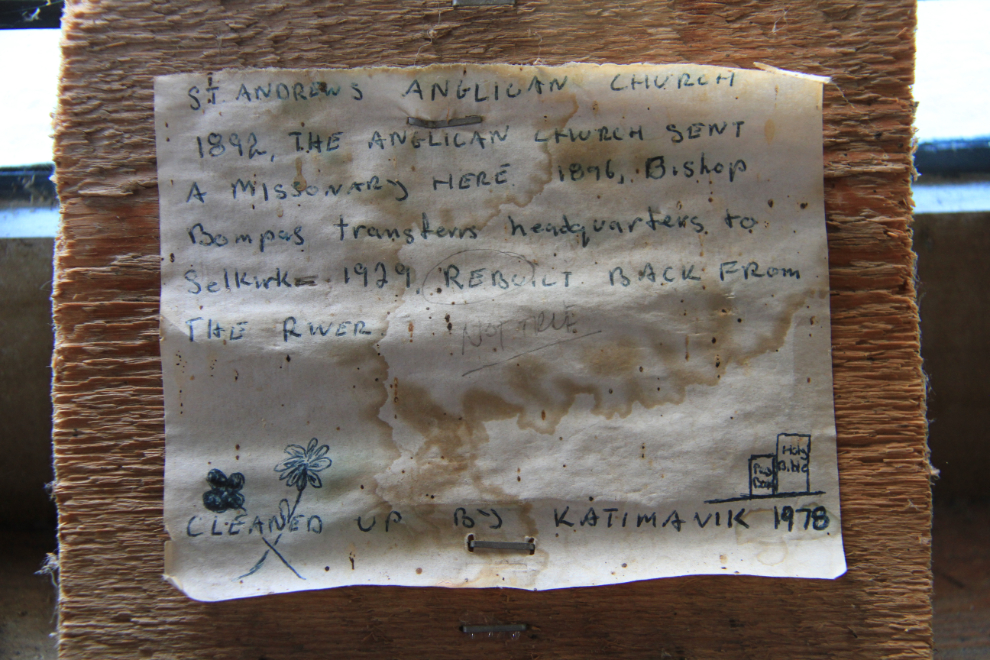

St. Andrews Anglican Church was built in 1931 of materials from the Yukon Field Force barracks. The building is the most elaborate one at Fort Selkirk, and the only one which was designed by an architect. The last resident minister, Kathleen Cowaret, moved to Minto in 1953.

The interior of St. Andrews.

In 1978, a new charity called Katimavik sent a crew of 17-20-year-old volunteers from all across Canada to Fort Selkirk to clean up the site and do some basic stabilization and restoration work. Some of the notes written by those Katimivik members have been preserved. The Yukon government started work on the site 6 years later.

Riverbank erosion has always been a problem for many communities, and it continues at Fort Selkirk. A large section of the bank in front of the school collapsed this year, and the building is now being moved further back from the river.

The interior of the schoolhouse. Built in 1892, probably by the Reverend Thomas Henry Canham, it’s the oldest known standing structure in the Yukon. It served as both a school and a place of worship until the church was built in 1931.

Looking back at the Anglican rectory and church from the schoolhouse. The rectory was built in 1893, also by the Reverend Canham, using squared, dovetailed logs. The front room also served as a winter school house, to save heating an extra building.

Upstairs in the rectory, newspapers glued to the walls as an extra layer of insulation in 1904 can be read.

A 7-man crew from the Selkirk First Nation in Pelly Crossing has been working on the site for several summers – the Selkirk First Nation co-manages the site with the Yukon government. Their most visible project this year is rebuilding the Taylor & Drury store’s stable.

One of my favourite buildings is the Coward Cabin. It was built in 1898 as the Yukon Field Force officer’s residence and is one of only 3 remaining Yukon Field Force buildings. Alex Coward moved the building from the Field Force complex in the 1920s – he was a well-known jack-of-all-trades who could build, move and repair anything. He lived in the cabin with his wife Kathleen Cowaret (Martin), the long-time Anglican lay missionary. Mr. Coward added this kitchen to the east side and a porch on the back.

The complex roof of the Coward home.

One of Mr. Coward’s tools. My guess is that this was part of a foot-powered tool-sharpening wheel.

Joe Roberts may have built this cabin around 1916, the date found on newspapers that were used as chinking between the logs. It was getting to be quite unstable, and vertical beams were bolted to each wall to keep it standing.

The interior of the Roberts cabin. One of the things about Fort Selkirk that is the most captivating to me is that it doesn’t feel like a “historic site” in the museum sense – although there are many interpretive signs, you’re free to wander, and very few things are in glass cases.

A broad view of the central part of Fort Selkirk, looking downriver.

Tommy McGinty built this tiny cabin in 10 days during the summer of 1939, at a time when he spent much of his winters trapping in the bush. A respected Selkirk First Nation Elder, he was a great source of stories, songs and lore about the traditional way of life.

This cabin, and the upper part of the cache, date to about 1930. The lower part of the cache was added about 10 years later. The Fort Selkirk booklet uses the names Luke Roberts and Robert Luke as their builder – it’s not clear whether that’s 2 people or 1 typo. 🙂

One of the artifacts in the cabin above.

Big Jonathon Campbell’s home is a reconstruction, as the original had been torn down following his death. It’s used as one of the 2 main interpretive centres.

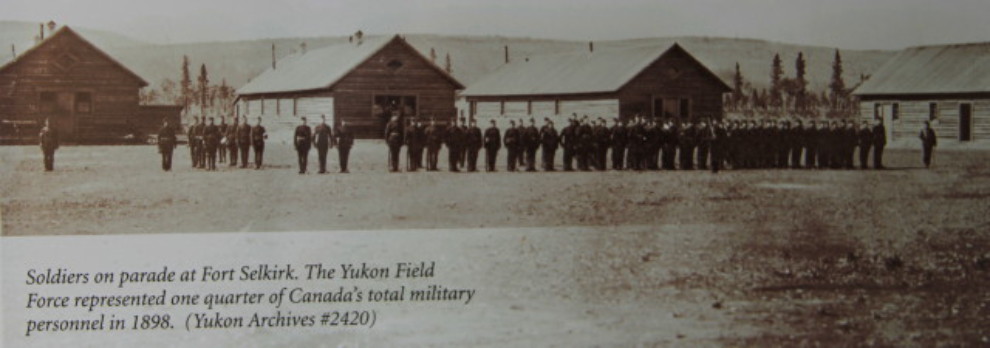

That brings us to the part of Fort Selkirk that was home to the Yukon Field Force in 1898-1899. Authorized on March 21, 1898 to support the North West Mounted Police in the Yukon, it was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Dixon Byron Evans of the Royal Canadian Dragoons, and consisted of 5 Staff, 16 Royal Canadian Dragoons, 49 men of the Royal Canadian Artillery and 133 men of the Royal Regiment of Canadian Infantry armed with Lee-Enfield .303 rifles, two Maxim guns and two bronze seven-pounder cannons.

The simple monument was erected by Canadian Forces members and cadets in 1972, on what had been the parade square.

Legend has it that these holes in the basalt wall across the river from the Yukon Field Force site were created by cannon fire practices.

There are 2 cemeteries at Fort Selkirk. In the one for non-Natives, the Yukon Field Force has their own section, with the graves of the 3 members who died while in service here: J. Corcoran, G. Hansen and H. Walters.

Other graves here are in various states of decay.

This collapsed cabin was built in the mid-1930s by Johnny Anderson following his marriage.

I’ll bet there are some interesting stories connected to this truck.

A scenic hill is the location of the St. Francis Xavier Roman Catholic Church. Built along the waterfront in 1898, this was the second Catholic Church in the Yukon – the log building uses French style piece-en-piece construction, which is unusual in the territory. It was moved to this site in 1942 by Father Bobillier.

The First Nations cemetery is very colourful but with a couple of exceptions the graves have no names or dates on them.

We picked a poor time to leave Fort Selkirk, as many others had the same idea. With only 2 shuttle boats, it took over an hour and a half to get on one. It had been a wonderful day, though, and the quiet bank of the Yukon River wasn’t a bad place to sit. At 5:20, this was our good-bye view.

We had had great weather all day – some hot sun, some clouds, a nice breeze to keep the bugs away. As we neared Pelly Farm, though, we could see ugly weather ahead. About 10 minutes from the boat launch, a storm hit us that brought icy rain down in buckets. Combined with the wind caused by the boat’s speed, it was miserable!