The Hammer Museum in Haines, Alaska

I always enjoy seeing people share their passion, and the Hammer Museum is a perfect example of that. The small building in downtown Haines that began life as a private residence a century ago now houses a collection of 2,300 hammers. As impressive as that number is, there are another 8,000 hammers that they simply don’t have room to display!

After several tries over many years, I finally found the “OPEN” sign in the window on August 20th, and Cathy and I went in for what turned out to be a lengthy look.

This wonderful bicycle made almost entirely of hammers is in the front yard.

The admission charge is $7 for adults, $6 off for active military, veterans, and their spouses, and kids 12 and under are free when accompanied by an adult. They have a website at https://www.hammermuseum.org.

Our visit started off well when Cathy asked the manager about the history of the museum. His eyes lit up, and over the next few minutes we learned the fascinating story as well as going down a few side trails 🙂 The museum’s founder, Dave Pahl, opened it in 2002 after collecting hammers for many years. Since opening, they have received many donations – thus the 8,000 hammers that they don’t have room to display.

The best way to tell you about the museum is probably to take you in a tour of it, so the next 24 photos show various hammers and display panels. The research that has gone into creating many of the displays is impressive.

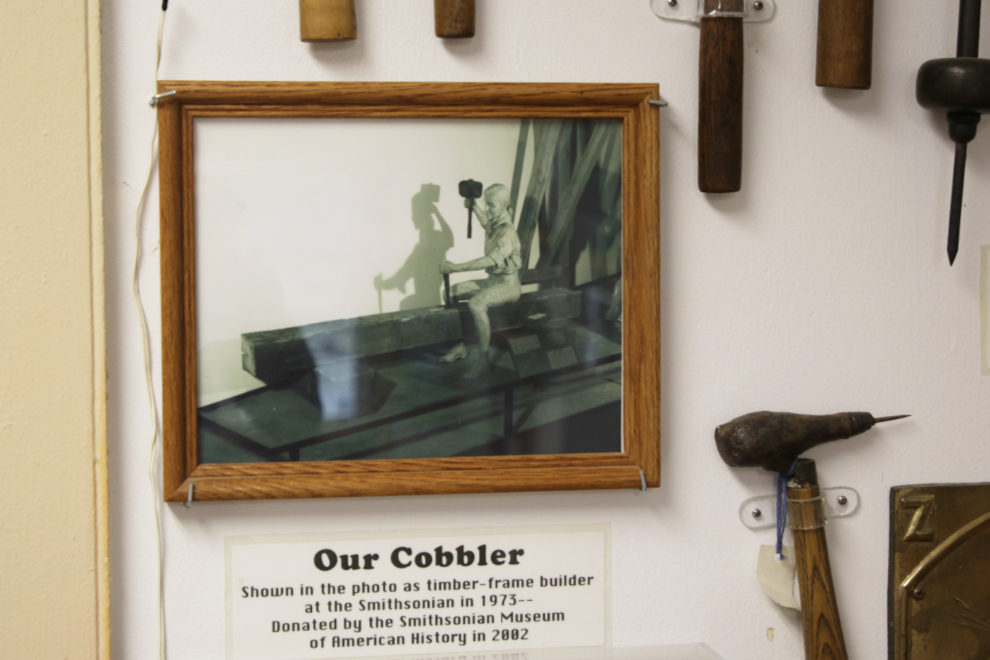

The life-size cobbler in the front room began life as a timber-frame builder at the Smithsonian Museum of American History over 50 years ago. When the Hammer Museum opened in 2002, the Smithsonian donated him and four others, and he now provides a wonderful start to the tour.

Some of the hammers on display are actually multi-tools, such as this intriguing box opener patented by G. C. Taft in 1851. The patent office listing for it doesn’t shed any light on how it was actually used.

Many of the hammers on display had specialized uses that never occurred to me, such as this autopsy hammer from 1862-1865. The display notes that “the hook [at the bottom] was used to pull off the calvarium (top of the skull) after it had been sawed through.” Changed little in 160 years, these hammers are still used – Surtex Instruments shows their current model and describes its use in more detail.

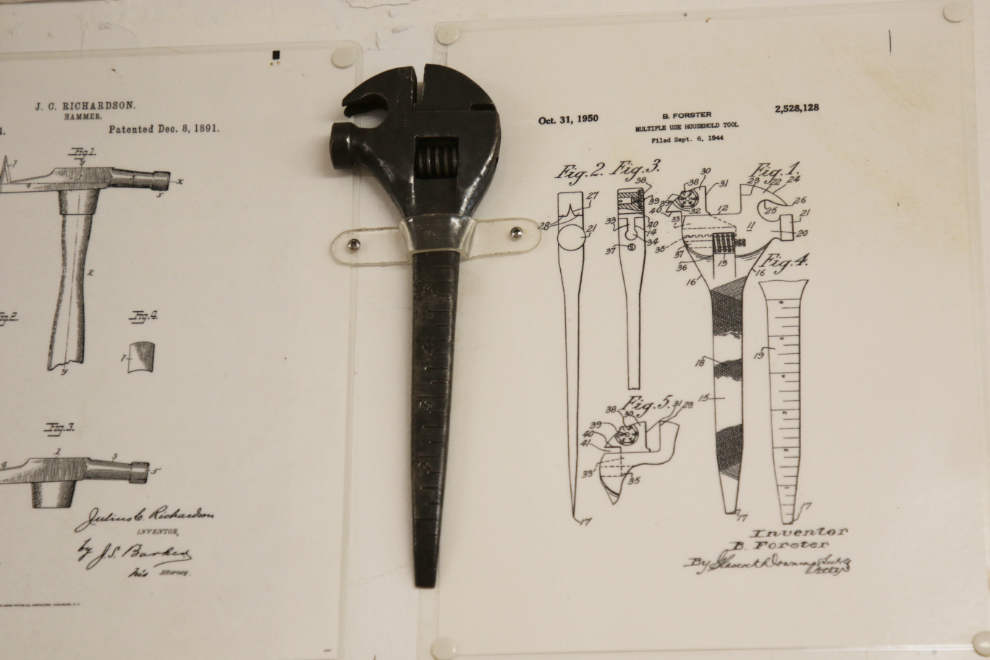

The next photo shows B. Forster’s “Multiple Use Household Tool,” patented in 1944.

There are several ancient war hammers or battlehammers. The large one on the left is a totokia from Fiji. The display states that it “was used for battle, human sacrifices, and tribal offender executions. The long, sharp beak of the hammer was used to ‘peak’ through a skull. This hammer was often buried with chiefs and high-ranking warriors.”

At the lower right of the next photo is a Tlingit slave killer / warrior’s pick. “This Tlingit artifact was found by Hammer Museum owner, Dave Pahl, in March 2002. He found it while hand-digging a basement underneath this building. Buried for centuries, this artifact is believed to be around 800 years old. It would have had an elaborately carved handle and would have been used ceremonially for sacrificing one or more slaves to be buried under the cornerpost when a new longhouse was built or with a chief when he died. It also would have been used as a warrior’s pick in battle.”

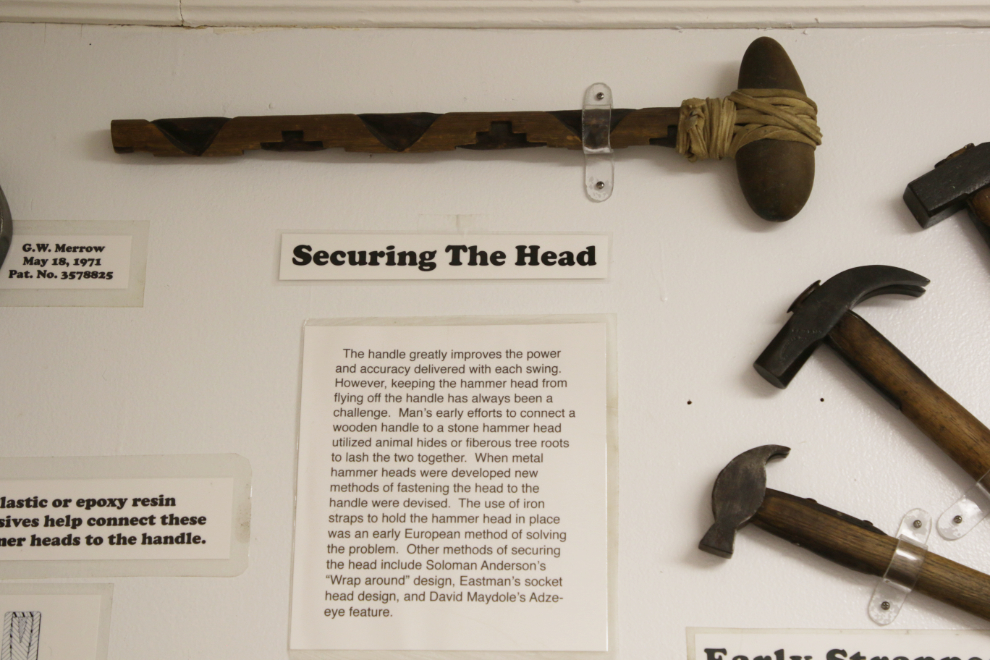

If you’ve used hammers much over a long period, you probably know that a solution to securing the head of a hammer to the handle hasn’t been found yet. The next display describes some of the methods tried.

“Hammer collector Don Stevenson is pictured in Fine Homebuilding Magazine (Nov. 1992), with his collection of 4,200 hammers. The Hammer Museum acquired his collection in 2007. We currently display 200 of his hammers in our museum, including the hammer he is holding in the photograph.”

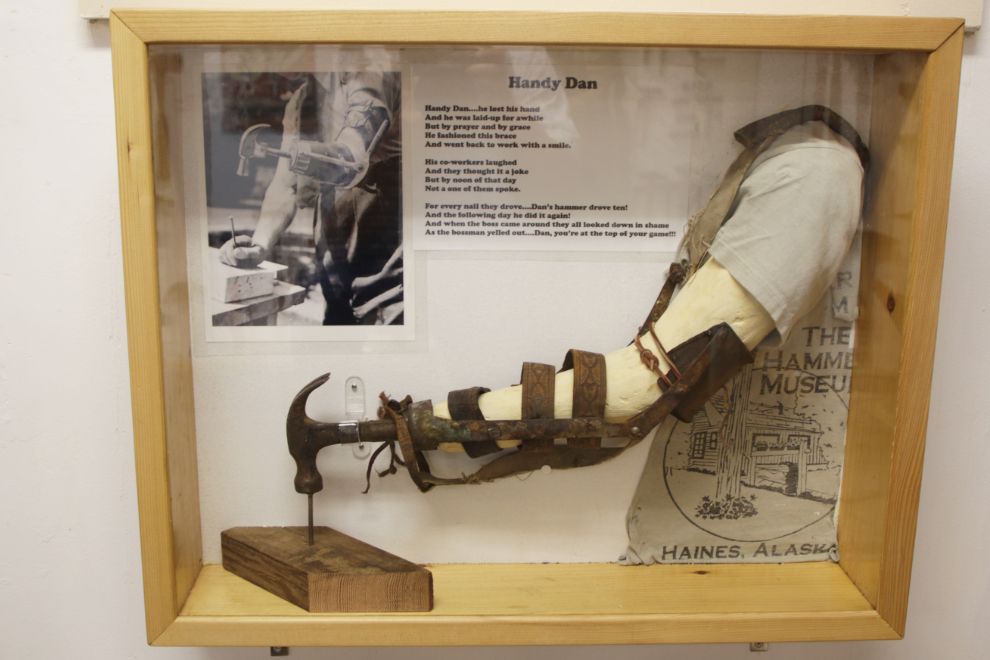

A hammer attached to an early prosthetic arm. The displayed poem indicates that it worked very well for “Dan.”

Nail-holding hammers prevent you from hitting your fingers, give you further reach, and allow a one-armed person to drive nails. There are over 182 patents for nail-holding features and attachments.

There was a special hammer made for use on the Rudge-Whitworth (Dunlop) knockoff wire wheels used on Jaguar, MG, Triumph and other British sports cars from 1907 until the early 1970s.

Although most hammers are made of metal, many other materials have been used, such as porcelain on this Meissen meat tenderizer.

There are also little wooden hammers used by guests to crack open crab in seafood restaurants.

Aluminum hammers cast with airline logos have been used to crack ice in aircraft galleys.

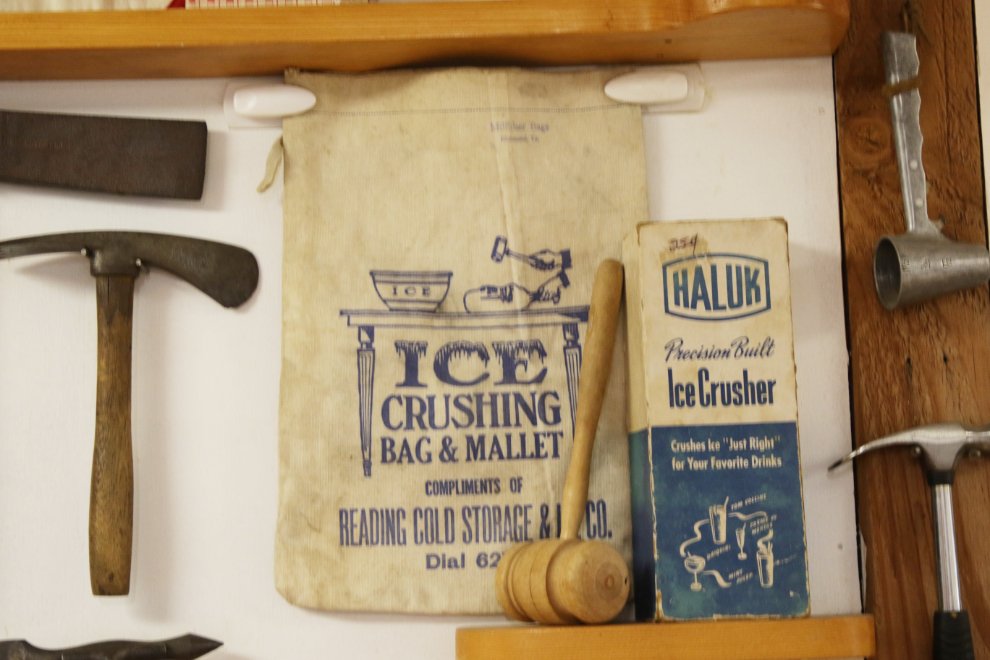

A wooden mallet used to crush ice in a canvas bag, from Reading Cold Storage in Reading, Pennsylvania.

There are hammers used for mountaineering, polo, croquet, golf, and other sports and types of recreation.

By the time I reached this busy corner, we had been in the museum for just over 40 minutes, and it was clear that another visit will be necessary. The collection is both fascinating and overwhelming. I should probably buy Dave Pahl’s book, “The Improved Hammer: A Guide to the Identification, History & Evolution of the Hammer” before my next visit.

Glass display cases hold some of the smaller hammers.

Back 40 years when I was doing antique vehicle restorations I had a few specialized hammers, but this wall showed me many I didn’t have.

Senior Master Sergeant Harold W. Porter was inducted into the Order of the Golden Hammer “for professional ability, technical excellence and personal skills in the art of aircraft maintenance” while assigned to the 60th Military Airlift Wing at Travis AFB, California.

A display of heavy metal working hammers, and much lighter chasing hammers for embossing. The description of how to use the chasing hammers properly is very interesting.

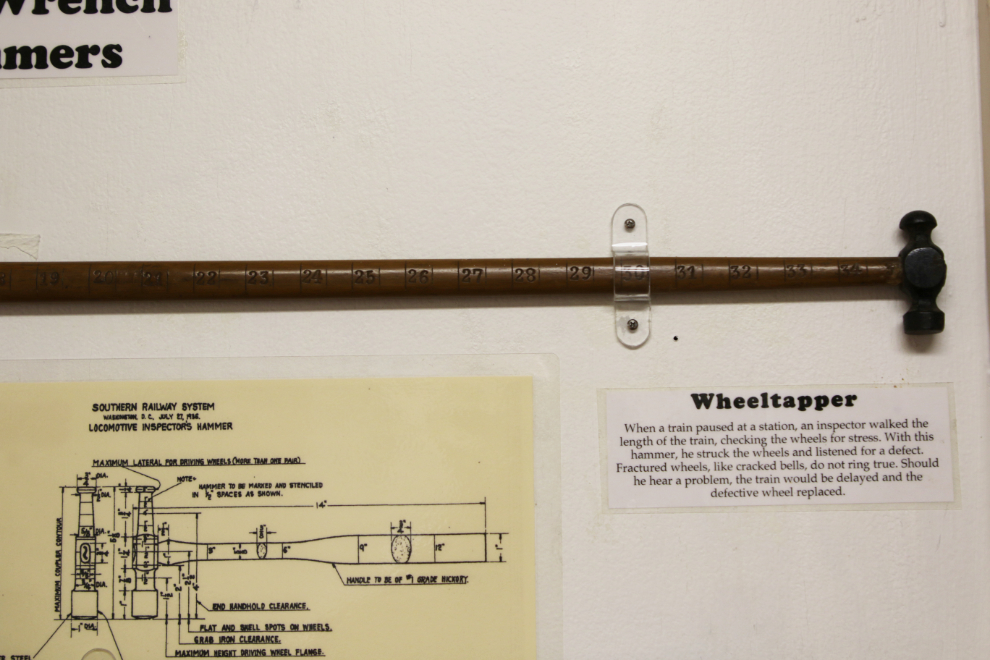

A railroad wheeltapper. “When a train paused at a station, an inspector walked the length of the train, checking the wheels for stress. With this hammer, he struck the wheels and listened for a defect. Fractured wheels, like cracked bells, do not ring true. Should he hear a problem, the train would be delayed and the defective wheel replaced.”

Below the wheeltapper is a wide variety of other railroad hammers, including tie-marking hammers, seal presses, carriage keys, and steam line disconnecting hammers!

When we left the museum after an hour, it wasn’t because I was “finished” but because my brain couldn’t absorb any more. Next time I’ll have more space cleared in there 🙂

I mentioned at the start of this post that this was the first time I had found the “OPEN” sign in the window of the museum. The primary change that caused that is the number of cruise ships that now visit. In the peak part of the season, Haines this year is getting an average of about 6 ships per week. Of those, two are large ships, two are mid-size such as the Regatta seen in the next photo (she arrived the day after our visit to the Hammer Museum), and two are small expedition-type ships. This provides enough visitors to keep some galleries and museums open (the Regatta brought over 100 visitors to the Hammer Museum), without changing the community in any noticeable way. My impression is that residents are happy with this level of cruise ship activity, and I hope that they don’t allow it to expand.

The Hammer Museum is becoming known as one of the must-visit attractions in Haines. Both Cathy and I agree 100%.

You ‘nailed’ this one!

Very interesting, as always!