By helicopter to Llewellyn Glacier and Lake No Lake, Atlin region

Friends and I have been trying for 4-5 years to get to unique glacial Lake No Lake by helicopter out of Atlin, but things just never came together – weather or schedules always got in the way. On Saturday, June 29th, though, four friends joined me on a charter I had booked. It was an incredible, mind-boggling experience. The variety of country seen on the circle route to and from the Llewellyn Glacier was so great that it’s taking me 57 photos to give you an idea of what the 2-hour trip was like.

We left my home just before 09:00. From here it’s 161 km to the Atlin airport, so we had a bit of time to stop along the way. Our second short stop was at the ancient terminal moraine of a long-gone glacier. Back in the ’90s when I taught night-school photography courses, this is where I used to take my classes for a final outing. It’s a wonderful place to experiment with both broad vistas and closeups, especially flowers. Mount Minto is in the background of the first photo.

With a few minutes still to spare, we detoured into downtown Atlin to experience the spectacular views. In the background of the next photo, the famous “rock glacier” flows down the slopes of Atlin Mountain.

I sure love it when things come together photographically just by luck. This is postcard Atlin 🙂

When we reached the Tundra Helicopters base, our pilot, Jamie Tait, was just cleaning the windows of his Bell 206 LongRanger – he said he’d been out killing bugs with it 🙂 Looking in my pilot’s log book, I see that I first met Jamie on June 18, 1985. I had flown into Atlin with 2 friends in my Cessna, and while exploring Atlin on foot, saw Jamie fuelling up his Cessna 206 float plane. While talking to him, he asked if we’d like to join him for a 2½-hour trip looking for forest fires. Hell yes we would! Jamie is a legend in northern aviation, and I was extremely pleased to be flying with him again.

As we were getting ready, I realized that I’d forgotten my Garmin inReach, which is very handy for mapping a complex trip like this.

At 11:15, after a safety briefing and getting everyone properly buckled in (the harnesses in the helicopter are much more complicated than your airline seatbelt) we were on our way! For the trip to the glacier, I got the front left seat.

At Pine Creek, signs of decades of placer gold mining can still be seen.

Looking down to a beach along Atlin Lake, through the window at my feet. As beautiful as Atlin Lake is from ground/water level, it’s even more so from the air, where you can see the amazing colours better.

Warm Bay – the warm springs are just out of the photo to the upper right. This is one of the must-see destinations near Atlin.

The mouth of the O’Donnel River. We were now leaving the road system behind and heading into some of BC’s finest wilderness.

Looking southwest across Simpson Lake.

Fifteen minutes from Atlin, Jamie said he had an Omnimax moment coming just ahead. He flew low and fast to a ridge and as we passed over it a huge new world did open up, though the increasing wildfire smoke in that direction did obscure it somewhat. The layers in the rock were amazing.

This river, seen seconds after the photo above was shot, isn’t named on any of my resources – it’s a tributary of the Sloko River.

Awesome flying, right down among the rocks so we could see the details.

We next looped around the wreckage of a US Coast Guard Grumman Albatross that crashed on June 15, 1967, while on a search for a missing aircraft. Three of the 6 people on board were killed. This was a story that I knew well as the result of a hike into the wreckage that 2 friends of mine, Kyle and Sara Cameron, made in 2017. It became a wonderful story when Kyle tracked down 2 sons of one of the victims, Robert Striff, and brought them to the crash site. Alexandra Byers did an excellent story for CBC about it last year, and “Out of the wreckage” can be read online.

It’s remarkable how much information you can try to cram into your brain on a flight like this. This lovely little waterfall close to the plane crash is only 21 minutes from Atlin.

Judging by the fact that there are no photos of it online, Sloko Falls is one of the most seldom seen large waterfalls in BC. I guess the fall to be close to 300 feet, and there’s a massive cave behind the wall of water.

A couple of miles upriver from Sloko Falls is milky-turquoise Sloko Lake. This is where the Camerons landed their float plane to hike to the Albatross crash.

The actions of glaciers thousands of years ago have created some unique places, like this meadow-filled hanging valley.

Here’s dramatic proof of how rapidly some of these glaciers are disappearing. For there to be no plants where the glacier used to be, this retreat has probably happened in just the past 20-30 years, and in another 20-30 years that glacier will likely be history.

Only 26 minutes from Atlin, we were getting close. The terrain, though there was still a great deal of variety, had the feeling of fairly recent glaciation, rather like the White Pass.

The hiking here would be incredible in many areas, and I started imagining getting dropped off in some of these places like the ones in the next 3 photos, for a few hours or a few days.

Our first view of Lake No Lake, at the right centre, 29 minutes from Atlin.

Closer and closer, my headset was full of exclamations from everyone about the sight.

Here is most of Lake No Lake, which appears and disappears often. The small river fills the valley behind the Tulsequah Glacier until there is enough pressure to break through the glacier, and it drains. It last broke through and drained about 10 days before our arrival.

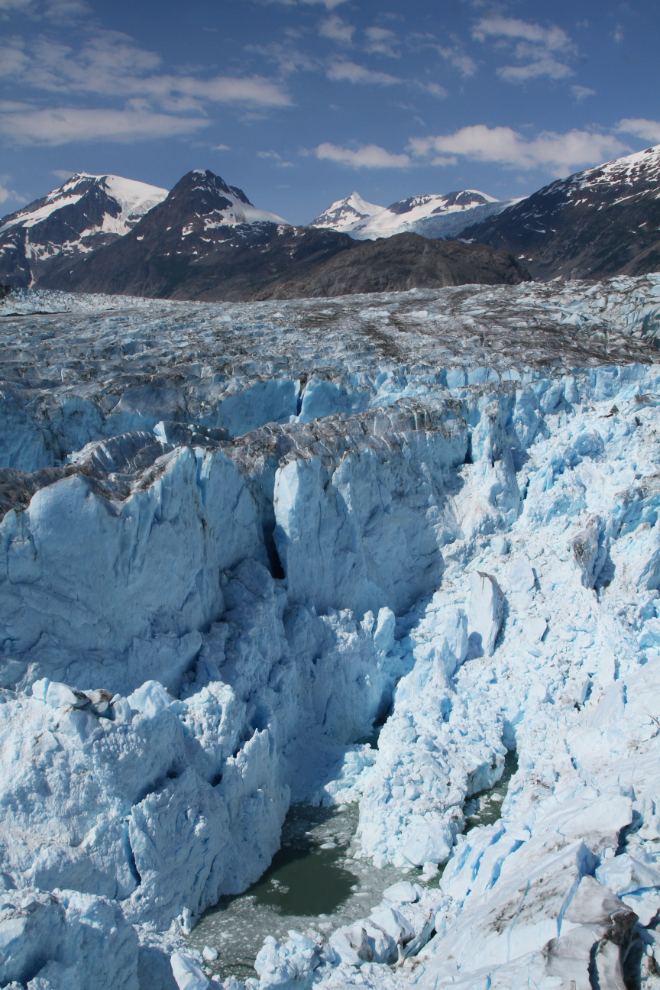

Before looking for a place to land, Jamie took us for a loop and and down the glaciers that create Lake No Lake. These are part of the Juneau Icefield, but I’ve looked for a map to see if they have names, with no luck yet. What maps I have found have just confused me, part of the problem being that the ice is disappearing so quickly that what we saw isn’t what most maps will show. The Juneau Icefield has 53 glaciers flowing from it!

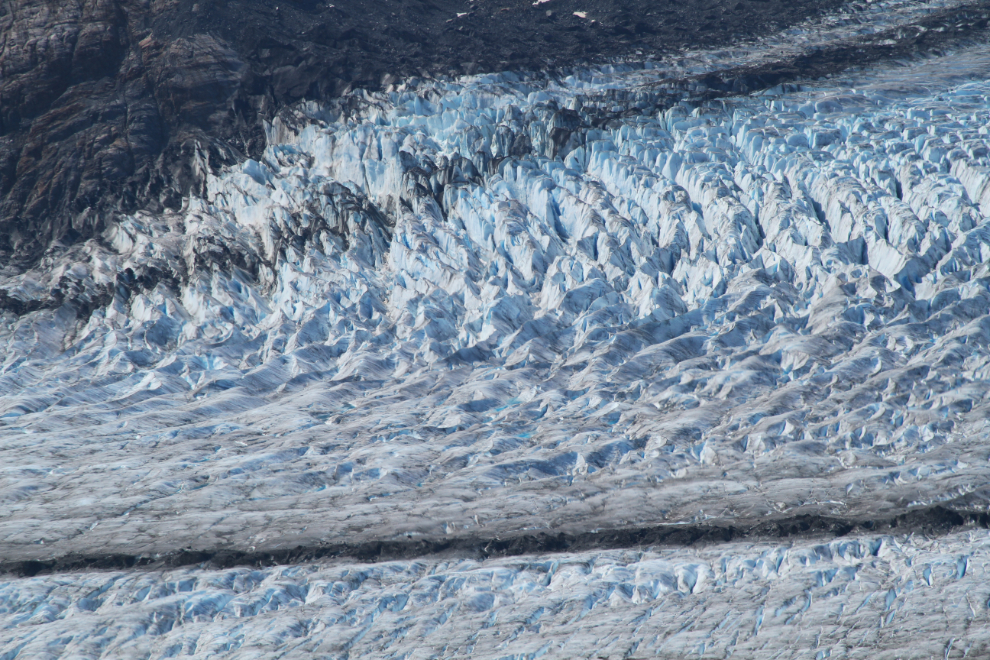

Glaciers fascinate me, both naturally and photographically. To think that a mass of ice can slowly flow down a valley continuously for thousands of years is mind-boggling, and the sculptures and patterns created by that flow and associated stresses are beautiful.

The 2 glaciers above join to form the Tulsequah Glacier, seen in the next photo which looks down-glacier. Its meltwaters form the Tulsequah River, which flows into the Taku River. Lake No Lake is immediately to the left of the point where I shot this photo.

The most dramatic of the peaks towering over us was the Devil’s Thumb, 2,767 meters high (9,077 feet).

Now it was time to have a good look at the feature we came to see. It had only been 33 minutes since we left Atlin. The spot seen in the next photo is where Lake No Lake drained, then the glacier collapsed and the lake is re-filling again. When it drains, it creates glacial outburst floods, or jökulhlaups, in the Tulsequah River – these floods from Lake No Lake have only been happening for about the past 50 years according to a couple of scientific reports I’ve found, but floods are getting larger in recent years.

The size of the some of the icebergs is incredible. We were flying below the top of the one in the next photo, which is probably over 100 feet high. With nothing to give a sense of scale (a tree, for example), it’s very difficult to judge either distance or size.

The colour of some of the ice that came from deep within the glacier was stunning.

Although landing down among the icebergs is the coolest experience, Jamie decided the lake was filling too rapidly to do that safely, so we landed above it. The high view was just fine 🙂

Between the 5 of us, there were a lotof photos shot from the little knoll we landed on! We really got lucky that the wildfire smoke that affected visibility for the first part of the flight had only minimally gotten into The Hall of the Mountain King.

This photo of me was shot by Xiu-Mei Zhang. I knew her so well from posts on the hiking group we both belong to that it took me a while to realize we hadn’t actually met in person before.

What a place to chill. Jamie said we could stay as long as we wanted.

Rocks and ice – the closeups were as wonderful as the broad views. A few times, we heard ice crashing around us somewhere – icebergs toppling down below, perhaps.

I took a short hike to get this photo of the helicopter with the broad view of the lake, glacier, and peaks. This was shot at 18mm.

After about 45 minutes, everyone had soaked up enough of the experience to satisfy them, and we got ready to depart. We lifted off 50 minutes after arrival. Things happen too quickly to do lens changes, so I had shot with my 24-105mm lens on the way to the lake, and switched to a 10-18 mm for the return trip. I was now in a back seat with Xiu-Mei and long-time friends Diane and Gary, while Karla got the co-pilot’s seat.

We would take a completely different route back to Atlin, but started with another loop among the icebergs and then a low pass up the creek.

Watching glaciers disappear is really sad. The Bear and Salmon Glaciers are the ones I’ve literally watched the retreat of over the past 44 years, and I transpose that experience to what is basically a remnant glacier like this one.

Another heli-hiking destination! This is no doubt serious grizzly country but what a place to spend a week. This photo was shot 7 minutes ater leaving Lake No Lake.

Two minutes further along, the terrain was much rougher but those lakes would be worth a fight to get to on foot. At the upper right you can see the trimline, the bare rock that marks the upper limit of the Llewellyn Glacier in the recent past (a few hundred years, I expect).

The next photo shows the Sloko River, but now we’re above Sloko Lake. This section of the river is only about 7 miles long, starting at a glacier, of course.

Eleven minutes from Lake No Lake, we reached the unnamed lake at the foot of the Llewellyn Glacier. The changes here are shocking – on the Google Earth image dated 9/10/2011, this lake doesn’t exist. It is on the Bing Maps image, which I don’t see a date on.

In June 2000, a helicopter crashed while filming a Nissan commercial further up the Llewellyn Glacier. The wreckage fell into a crevasse, and it was deemed too dangerous to attempt to recover the bodies. In July 2001, though, a private team was able to recover 3 of the bodies. Recently (I haven’t found an article about it), the glacier’s advance has brought the wreckage to a point where a camera that had belonged to one of the film crew was recovered and its card still had a a video selfie recorded by the owner.

At 1:00 pm, 14 minutes from Lake No Lake, we turned away from the power of the Llewellyn Glacier and hopped over a low ridge and then climbed up for a higher view of the peaceful beauty of Atlin Lake. In just a few seconds we had returned to a completely different world.

The brilliant colours, the gorgeous beaches with not a person or boat in sight – Atlin Lake is indescribably beautiful. Looking down at one particular, I said aloud that I need a houseboat. Once I got home and started thinking about it a lot, though, it’s a floatplane I need 🙂 – not just for Atlin Lake but for the entire North country. While I can afford to get another plane on wheels, though, floats are a whole different ball game 🙁

The next photo was a grab shot as we zoomed past “an island on a lake on an island on a lake”, as Jamie explained it – an island on an unnamed lake on Teresa Island which is on Atlin Lake 🙂

At 1:18 we were back over Atlin – this high view was followed by a lower, high-speed pass along the waterfront, then we returned to the airport. We landed 2 hours and 6 minutes after we left.

On the drive home, we stopped along Little Atlin Lake, and were greeting by this beautiful large butterfly, a White Admiral (Limenitis arthemis). We have about 91 species of butterflies in the Yukon.

The beach we stopped at was in a large shallow bay, and the water was very warm. Wading around there was a wonderful way to end our Atlin Adventure 🙂

The research need to write this blog was the most intensive I’ve had to do in a long time, and even then I just skimmed the surface. Now, though, I know enough that I want to go back! Luckily, I know other people who want to go 🙂