Crowsnest Pass – beauty, mining history, and great tragedies

Although we didn’t have a specific destination in mind when we left Sparwood, exploring historic sites through the Crowsnest Pass was the plan for Day 29 of our RV trip – Thursday, May 24th.

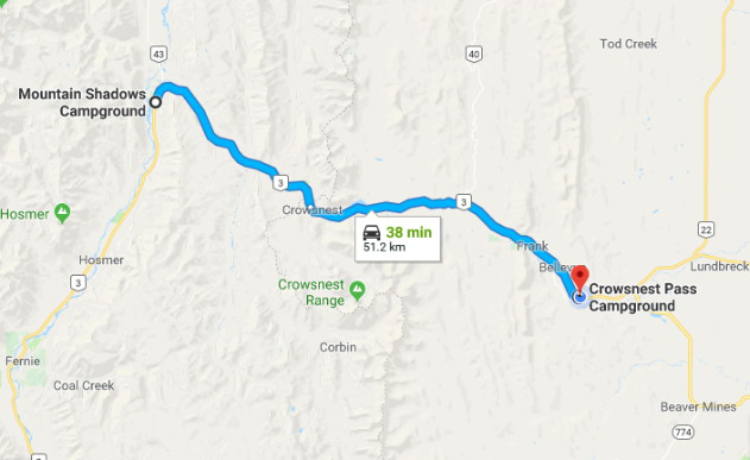

While we did a lot of exploring, we only put 51 km on the motorhome, from Sparwood, BC, to a campground just east of Bellevue, Alberta. Click here to open an interactive version in a new window.

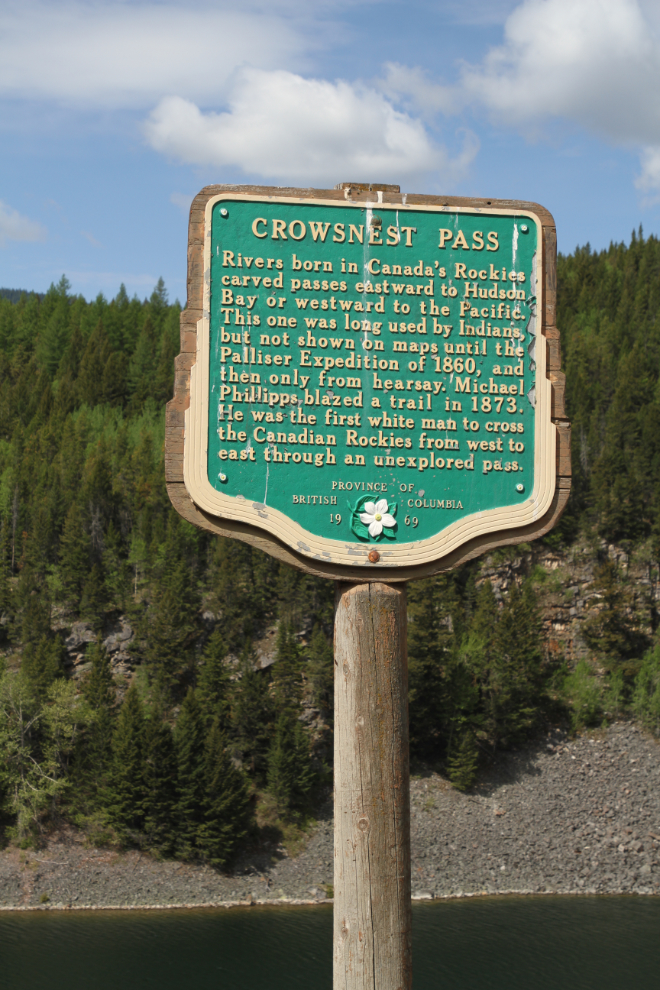

This Heritage BC Stop of Interest sign at the summit of Crowsnest Pass (1,358 meters/ 4,455 feet high) describes a bit of the pass’ early transportation history:

Rivers born in Canada’s Rockies carved passes eastward to Hudson Bay or westward to the Pacific. This one was long used by Indians, but was not shown on maps until the Palliser Expedition of 1860, and then only from hearsay. Michael Phillipps blazed a trail in 1873. He was the first white man to cross the Canadian Rockies from west to east through an unexplored pass.

The terrain starts to change rapidly as you travel east from Crowsnest Summit and pass into the rain shadow of the Rockies. This is the view back to the west from the summit.

My first goal of the day was actually to find some water to cool Bella off – she’s so uncomfortable in this warm weather (the weather was forecast to be 28°C/82⪚F again). A few lakes shown on the maps offered possibilities, and I had vague memories of Island Lake, just across the Alberta border, offering good possibilities – Highway 3 goes across the middle of the lake. Island Lake Provincial Recreation Area proved to be perfect, and we had a good long play in the very chilly lake.

Island Lake may also be a camping place on our next trip through the Crowsnest – the Recreation Area campground has 41 unserviced sites along what feels like an old airstrip, for $18 per night.

Just after 1:00, we stopped at a huge pullout for lunch. Across Crowsnest Lake, we could see the Summit Lime Works. A group of Italians had been making lime with a pair of beehive kilns here, but in 1903 Dr. E. Hazelle bought them out, formed Summit Lime Works, and moved the plant west to a location where the Canadian Pacific Railway could build a spur line. Now owned by Graymont, the company is still shipping high-calcium lime and limestone now, 115 years later.

We stopped at the Travel Alberta Crowsnest Pass Visitor Information Centre to get more detailed information about the options were for the next couple of days, and Janet Martin, who once worked in Dawson City, was extremely helpful. The Centre is very RV-friendly and even has a picnic table.

This was the view back to the west as we returned to Highway 3 from the visitor centre.

We had a good long visit to the Frank Slide Interpretive Centre during our drive through the Crowsnest Pass two years ago, so didn’t repeat that this time. The Frank Slide, though, is still a dominant feature of the valley for many miles, 115 years after the tragic event. The sign seen in the next photo is at a pullout along the highway.

The historic Bellevue Coal Mine is very visible from the highway, and every time I go by, I tell myself that I need to do their underground tour. This was the year, and it was #1 on my list of things to see and do in the Crowsnest. Having worked underground at Granduc Copper for a few months in 1975, I never pass up an opportunity to go back into the darkness.

There’s no date on this large photo of the Bellevue Mine hanging in the office, but it appears to be from about 1910-1915. The town of Bellevue was founded in 1905 on the flat land above the mine, which was operated by the West Canadian Collieries (WCC). None of the structures in the photo seem to have survived.

I bought tickets for a tour which would start in 15 minutes, for $35 for the 2 of us. A staff member brought a wheelchair out to the motorhome to make the underground tour much easier for Cathy. Properly kitted out with hardhats and miners’ lights, we were soon at the adit – the concrete face dates to 1928. We had also put on warm clothes – the temperature underground is from 0 to plus 2 degrees C year-round.

Our underground guide, Mel, did a great job of explaining the mine – the technical sides of getting coal out of this particular mine, and also the personal stories of what it was like to work here.

This section of the mine is quite disorienting, with none of the timbers being vertical. There’s a fair bit of water running in this section of the mine, and Mel said that in the winter, icicles would give a good vertical perspective.

There was no artificial light in the mine except the narrow beams from our miners’ lights. Here, coal came down a chute into the waiting coal cars, which were moved by men and horses.

Although these 2 miners had lots of headroom in the chute area, in much of the mine, the ceilings were very low. This was a dangerous occupation. Methane gas in particular could build up with tragic results – an explosion in the Bellevue Mine on December 9th, 1910, killed 30 of the 42 miners working, and one miner on the rescue team.

Near the end of our tour, the colours in this wet wall of seeping minerals were quite incredible. The miners working here would have, of course, wanted to see no colours other than coal black.

Back in the sunshine at 3:30, with the Frank Slide visible in the distance.

Having now visited two of Alberta’s three worse disaster sites, I wanted to visit the third, so the Hillcrest Cemetery and the Hillcrest Mine Disaster Memorial, less than 3 km away by road, was our next stop.

We began our visit at the Hillcrest Mine Disaster Memorial Park, a circle walk with about 20 interpretive panels describing the explosion that killed 189 miners on the morning of June 19, 1914.

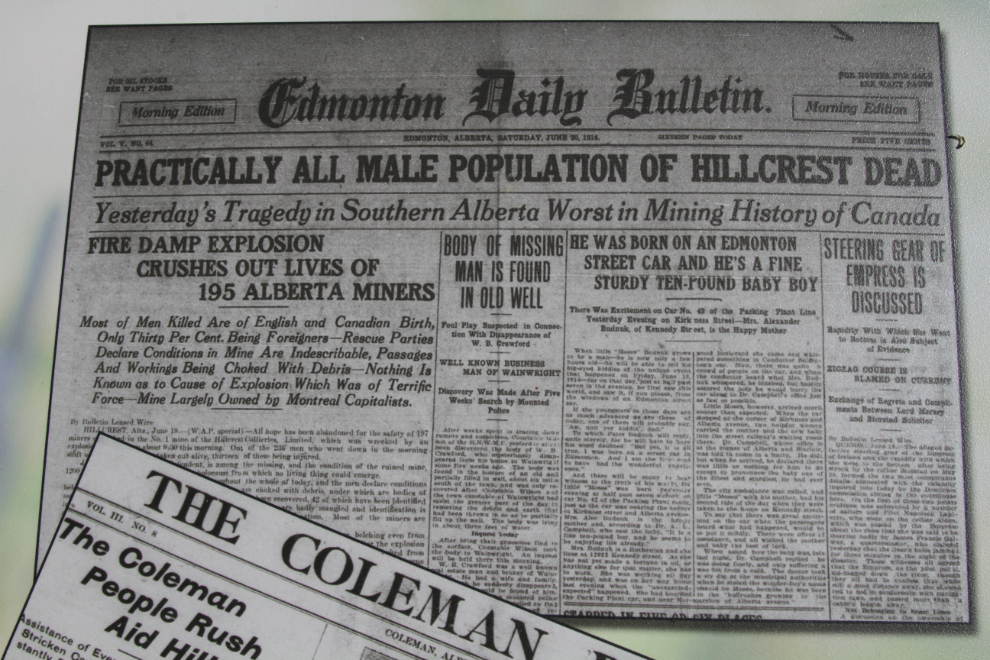

This newspaper copied on one of the interpretive panels gives an idea of the scale of the tragedy. It remains the worst mine disaster in Canadian history, and at the time, it was the third worst in the world. Only 46 miners made it out of the mine alive on that awful day.

We spent a long time in the memorial park, reading each panel and trying to absorb it all, and trying to imagine what the impacts must have been. The impacts on the families, the community, the region, and on the entire mining industry.

This photo on one of the panels shows the largest of the mass graves for victims being dug.

Looking from the fairly small parking lot up to the main memorial, with the Frank Slide towering behind.

The black marble memorial at the center of a circle with benches around it – a fine place of contemplation and to pay respects. The names of each man is listed, and perhaps an explanation for the mass graves (though not all victims were buried in Hillcrest, and some have seperate graves): “As they had worked, so they were laid, shoulder to shoulder in common graves.”

Around the Hillcrest memorial, 17 black marble tablets list Canada’s worst coal mining disasters (killing 3 or more men) between 1873 and 1992.

Most of the Hillcrest Cemetery, which is still in use, looks like any other cemetery, with a lovely mountain background.

This is the largest of the mass graves for the mine victims. It’s located near the back of the cemetery. Around it is a steel fence, and there are several more interpretive panels.

Many of the mine disaster victims have no grave marker, but a brass plaque for each man is on the fence, whether there is a marker or not. Only one body was never found in the Hillcrest Mine, but Sidney Bainbridge is also remembered here.

On these panels overlooking the largest mass grave are brass plaques for victims buried elsewhere in the Hillcrest Cemetery, or in other places, as well as a cemetery map. To me, this was the most powerful location, but perhaps that was at least partly because of the light. For anyone interested in Canadian history, or mining history, I highly recommend a visit to this memorial site – it’s exceptionally well done.

From here, our Crowsnest Pass visit would focus less on history and more on beauty (though history is inescapable in the Crowsnest).