Canoeing to a World War II pipeline pump station in the White Pass

In the afternoon of July 3, my friend Greg from Haines arrived at my home, and we took the motorhome to the White Pass for a 4-night stay so we could go canoeing and hiking. On our first outing on July 4th, we canoed to the head of Summit Lake and made a short hike to the ruins of a Canol pipeline pump station along the White Pass & Yukon Route rail line.

I set up camp at my usual spot just south of the Summit Creek bridge on the South Klondike Highway. Although it’s right beside the highway, this part of the highway between the Canadian and American border posts is closed from midnight until 08:00. Even during the day, traffic is fairly light.

There’s a lengthy section of newly-resurfaced highway north of Fraser. It still has a lot of gravel on it, and a semi tossed a large one into my passenger-side windshield. It’s much too large to fix, and each side of the 2-piece windshield costs a few dollars short of $2,500 to replace. It’s the cost of having fun, but ouch.

Right across the highway from the RV, behind a rock bluff, is this lovely series of ponds that make a wonderful spot to have a morning coffee.

At about 09:30, I unhooked the Tracker from the motorhome, and we drove a mile north to launch the canoe at a spot where the highway goes close to the lake (there’s no boat launch on Summit Lake). I paddled up the lake, and Greg drove back to Summit Creek and walked down to meet me at the beach at the mouth of Summit Creek. By 10:30 we were well on our way up the lake. The plan was to beach the canoe near the head of the lake, about 4 km from Summit Creek.

I’ve opened an account at Ramblr, and an interactive map of this trip is now there titled “Summit Lake – WWII pump station“.

We found a good spot to beach the canoe near the site of the Canadian Shed (more about that later), and we climbed up above the railway. There are still artifacts and wreckage dating right back to the Klondike gold rush all over this area, and trying to guess what it was is part of the fun for me. In the next photo, the railway is on the left and the head of Summit Lake can be seen in the distance.

One train arrived at the summit shortly after we did, and when another arrived, the first one backed up to our location to let the other one do the necessary switching. Most people off the cruise ships just take the shortest train ride, to the summit and back to Skagway. At the summit, the locomotives are moved to the opposite end so they’re back at the front of the train for the trip down.

What a surprise when the WP&YR crew member (conductor?) turned out to be someone that Greg knows from Haines! Mike came over and we chatted for a couple of minutes while the switching was being done. The passenger car behind Mike is one of 2 luxury Club Cars on the line now. I got to ride in one in 2014 on a special trip to honour my long-time friend Boerries Burkhardt, a dedicated WP&YR railfan from Germany.

The next photo looks north at the site of the Canadian shed, a 1,064-foot-long snowshed that was demolished in the 1980s.

We walked along the granite above the rail line, and there was wood everywhere, I expect much of it from the snowshed. The next view looks south at the Canadian shed cut.

Most of the pipeline between Whitehorse and Skagway was removed in the late 1990s, but small sections can still be found in many locations. A brief history of this pipeline follows.

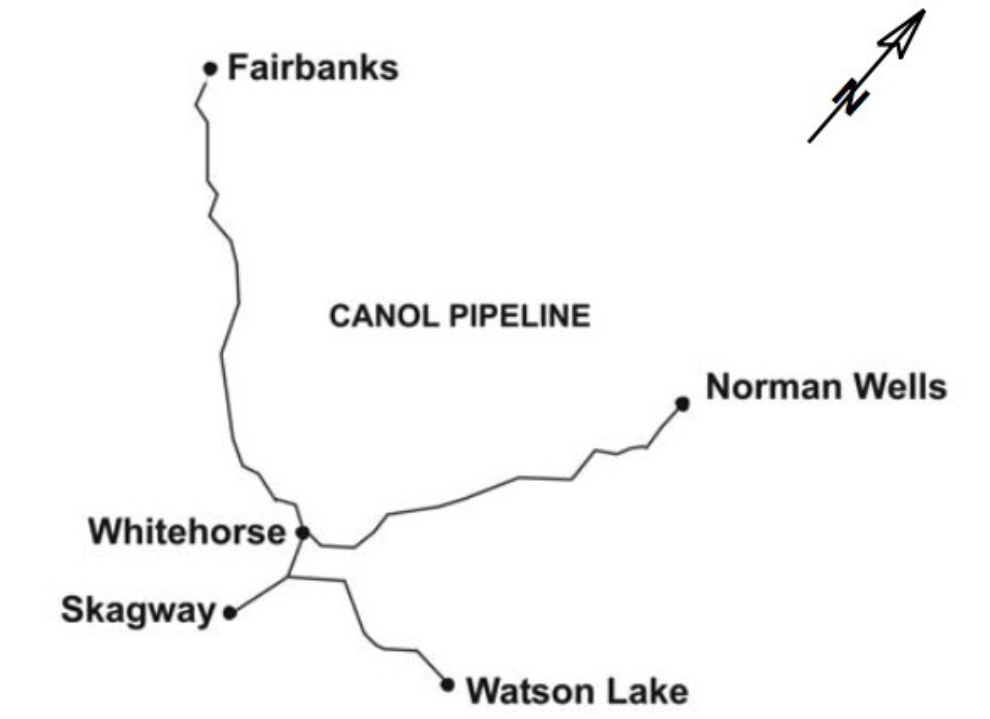

In 1942, the US army constructed a 4½-inch OD above-grade pipeline (Canol No. 2) from Whitehorse to Skagway. This pipeline, a tank farm in Whitehorse, and pump stations at Carcross and Summit Lake, comprised part of the larger Canol pipeline project, constructed to transport, refine, and distribute liquid hydrocarbons from Norman Wells for use in the Yukon and Alaska during World War II. The US army owned and initially operated the facilities. The White Pass and Yukon Corp. began operating Canol No. 2 in 1947, reversing the flow to supply Whitehorse and the Yukon with gasoline, diesel, and fuel oil shipped by sea to Skagway from Vancouver. In 1949, the US army resumed operating the pipeline, transporting White Pass fuels as well as their own. White Pass purchased Canol No. 2 from the US and Canadian governments in transactions from 1958 to 1961 and became the sole shipper via the pipeline. White Pass operated the Canol No. 2 pipeline from 1962 until 1994 with only minor modifications, and it was then shut down.

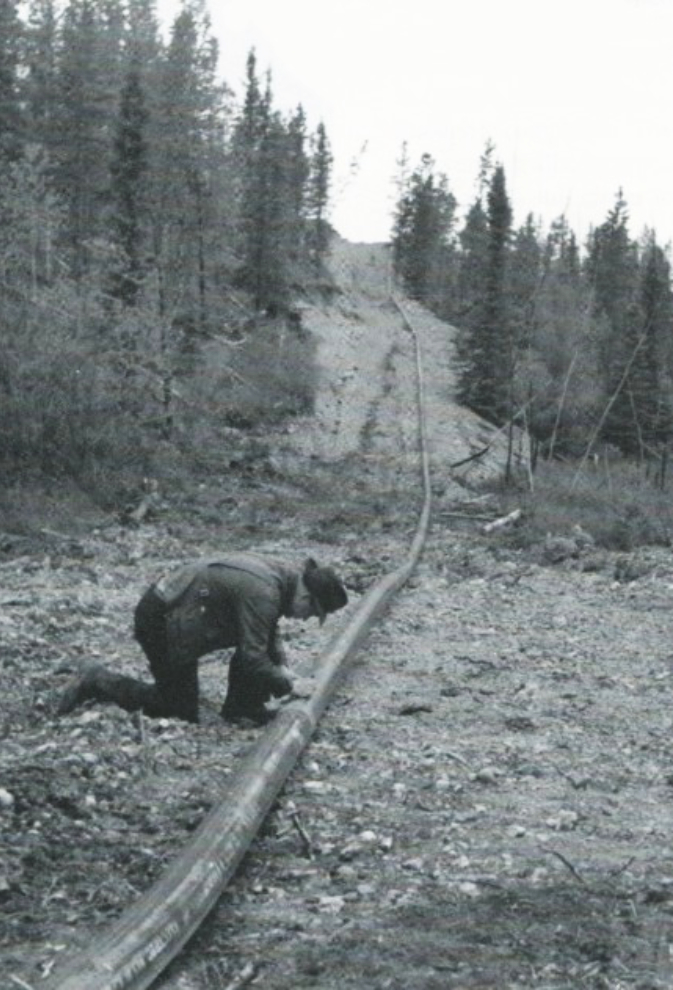

Pipeline technology was in its infancy. Pipe was simply laid on the ground and welded. Spills were common and often very large. The photo below (National Archives of Canada, Finnie collection) shows a section of the 6-inch main pipeline from the Norman Wells oilfield to the Whitehorse refinery.

At the pump station site just north of the Canadian shed cut, this wooden tower is the only thing visible from the rail line now. Carl Mulvihill says in his “White Pass & Yukon Route Handbook” that this structure was access to a pipeline pump valve – it’s high because of the deep snows there.

The sight of a few blocks of concrete lured us further from the rail line.

This is the foundation of the main pump station building. I have not yet found any information about this pump station other than the fact that it was part of the initial Canol construction. So much to research, so little time…

A closer look at the primary foundation.

This great little freight wagon is still sitting there, saved by its very remote location.

This garbage dump is right beside the pumping station foundation.

This is a sampling of the bottles that are laying around – the middle one is a very distinctive ketchup bottle. We didn’t remove anything from the site.

A broader view of the site. I should have had the drone to get a good look at it all.

Several other buildings were scattered over quite a wide area around the pumping station.

Walking back towards the canoe just before noon, two trains arrived from the north, fairly close together.

Having a train in the Canadian shed cut makes it easy to see that building a roof over it to keep the snow out would have been a fairly simple job.

Very pleased with what I’d found, we paddled back down Summit Lake in search of a route to an unnamed valley to the east. That search would take us 2 days.