A Whitehorse Copper Belt railway hike

Last week, Tim Green offered to take members of my Yukon History & Abandoned Places group on a guided hike of the Copper Mines Branch of the White Pass & Yukon Route railway. On July 2nd, 8 people and a St. Bernard joined him – we walked a total of 8.1 km at 8 locations, joined by driving, in just under 5 hours. You can see the stops on my Strava page – only the walking sections were logged with the app.

The Copper Mines spur line ran 18 kilometres from a junction with the main White Pass & Yukon Route line at McRae on the Alaska Highway to the Pueblo Mine on what is now the Fish Lake Road. An investigation of the route was made in August 1907 By White Pass Superintendent V. I. Hahn and railroad surveyor P. F. Wright of Seattle. The Weekly Star of August 23rd said in part:

As the proposed route is through a practically worthless country aside from its mineral values, and that will be greatly enhanced by the building of the road, the trouble sometimes met with by railroads in securing a right of way will not be confronted in this case, as without the road the territory penetrated is of no real value to anyone for any purpose. But with a railroad, however, it may some day possess some

value.

Construction began in October 1907, but after nearly 10 kilometres of rail bed and 7 trestle bridges had been completed, work was halted in July 1908 when copper prices dropped and all the mines stopped shipping. Construction began again in March 1910 and the rail line was completed in August of that year.

Ore shipments on the line stopped in 1918, and by 1927 it was no longer usable. Rails and bridge timbers were salvaged by the United States Army during construction of the Alaska Highway, and the materials were used to expand railway sidings at Cowley, McRae, Wigan, Utah and Whitehorse. When mining resumed in the late 1950s a road was built on about 11 kilometres of the railway roadbed. Today, there is little to see without a knowledgable guide.

At 11:00, we met at a section of the rail line just off Moraine Drive, at the north end of the Whitehorse Copper country residential subdivision. There are 2 interpretive signs there about the copper belt and the railway – you can see them and read the text on my RailsNorth.com website.

Here, Tim gave us an introduction to the rail line. He has a website with lots of information including photos and a map, at https://then.timmit.ca/projects/cmbranch/index.shtml.

We were standing on the old rail line in the next photo, but some old brush piles from land clearing made getting to a good section of the line rather difficult.

Dropping down to the rail line from the brush piles.

The Yukon Government says this interpretive sign about the White Copper Belt is at Km 1128 of the Alaska Highway, but the highway is a long gnarly way from here! You can see the sign and read the text at RailsNorth. We were now 30 minutes into the tour, all on foot.

Just 3-4 minutes after leaving that sign, we were scrambling down into a deep gulley to look at some bridge remains. A fairly lengthy article in The Weekly Star of July 3, 1908, said that in the first 3 miles of rail line from McRae “there are no less than a dozen bridges, the largest being 535 feet in length and of crescent shape, the entire bridge constituting a half moon curve. At places it is forty feet high. It spans a dry but deep gully. Other bridges are from 60 to 200 feet in length…” Read the entire article here.

Climbing up the other side to the northern abutment of that bridge.

There are lots of artifacts at this second location, including timber bolts and steel spacers, and railway spikes.

This was a one-way route as it ends at a beaver pond, so we had to return to our cars the same way. Through the gulley, there is no trail – I shot the next photo looking down on the group from the top of the first abutment.

Back at our cars, we made the short drive to Mt. Sima Road, where a gated road leads to the site of the Whitehorse Copper mill, built by New Imperial Mines in 1967.

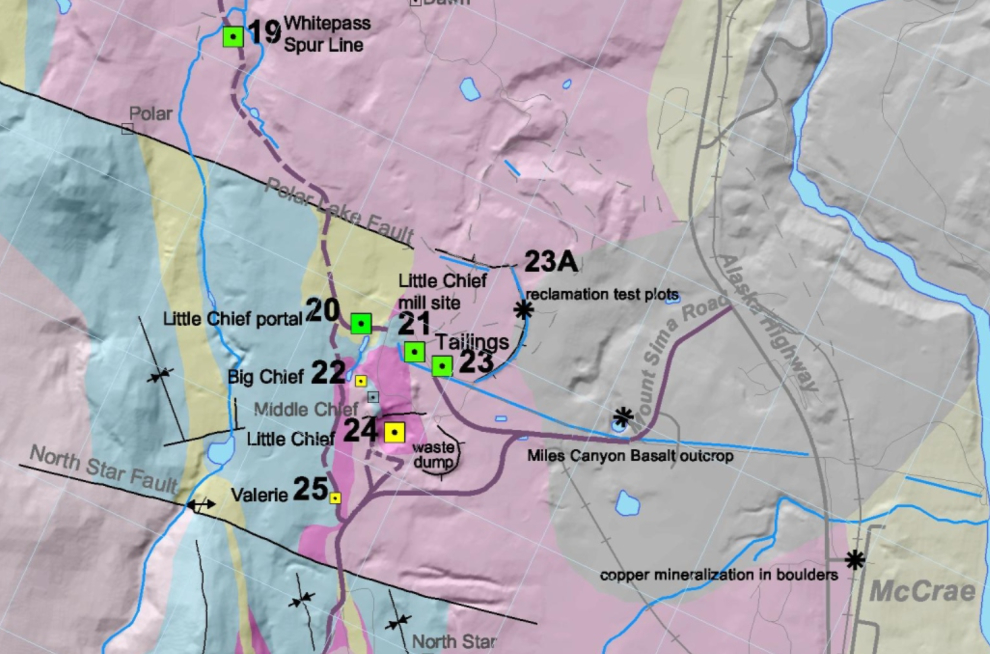

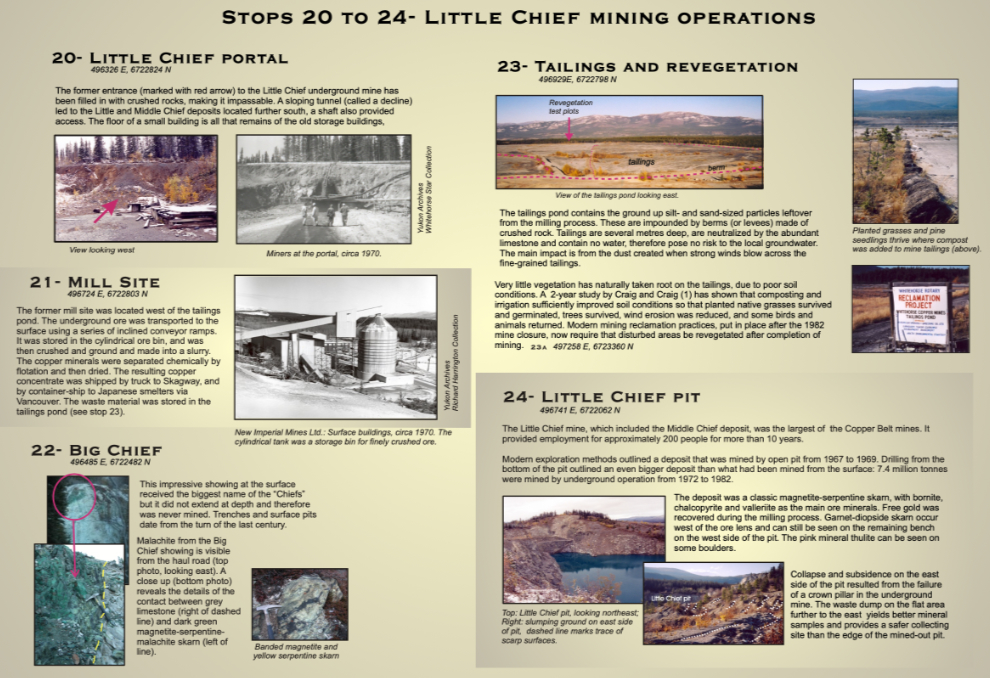

The Yukon Geological Survey has published an extremely good Whitehorse Copper Belt geology and history map and guide that was created by Daniele Heon in 2004. With these, you can do a very good tour of the copper belt on our own. Download both at https://data.geology.gov.yk.ca. The next two images are screenshots from the map and the legend.

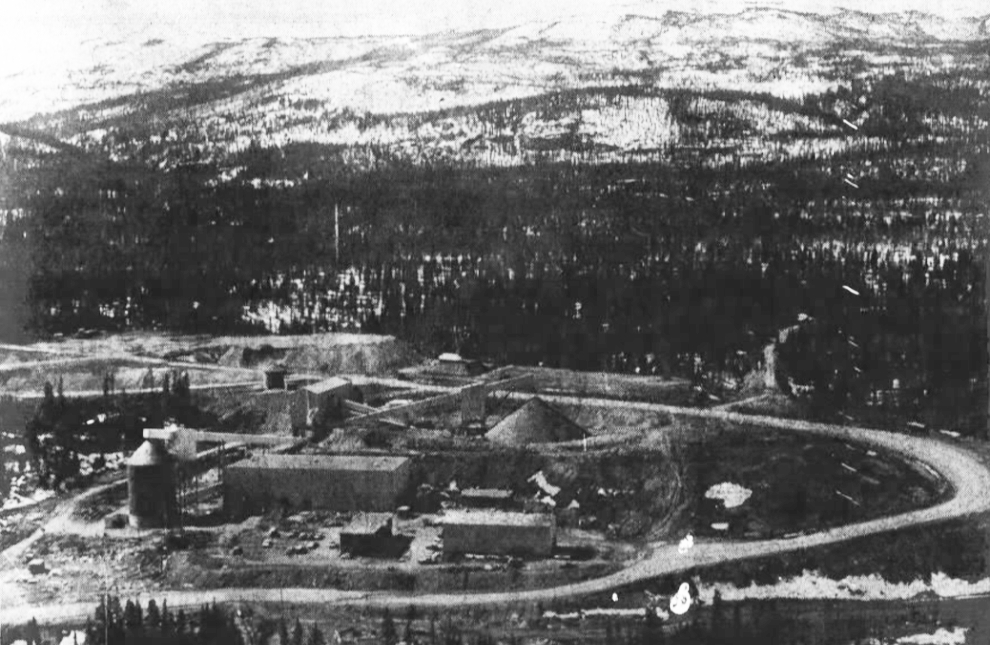

Here’s an aerial view of the mill area in June 1967. Whitehorse Copper closed in December 1982, and cleanup of the site began immediately but the final buildings weren’t removed until the early 1990s. Several proposals have been put forward over the years to re-process the tailings but little was ever done.

The railway looped around this area to gain altitude before heading further north. The parts that became roads are still visible but other sections have completely disappeared.

The next move by car was very short – it took us to the edge of the mine site above the old mill site and tailings.

I forgot to make a note of what was significant about this spot – but after seeing this comment, Tim sent me an email: “This is right on the path of the railway. There was a timber bridge here to carry the railway over a wetland. When the mill was in operation, this became the main route for ore coming in from the Copper Haul Road with a causeway of waste rock replacing the timber bridge. In the picture, we are standing on the causeway.” Thanks, Tim – teamwork! 🙂

A panoramic look at the tailings ponds.

The next photo was shot by Julie Ourom – I’m on the right. It was now 1:30 and we took a lunch break here. I was starting to feel sick (brain-sick) and almost quit here, but I really wanted to see what else Tim had in his goody-bag of history so decided to push through it as long as I could.

Continuing on, we drove mostly on the old railway grade, now the main road through the mining area, to the site of the Carr Glynn railway station and water tower, just above this lovely little lake.

This is the only building depression in the area so may have been the site of the Carr Glynn station, though it’s quite small. In February 1913, The Weekly Star noted that Mrs. Dahline of Skagway was working there, presumable as the cook and housekeeper, and her daughter Bernice had come up to visit her.

The large number of tin cans at the Carr Glynn site show that there was a fair bit of activity here.

Our next stop, with a short walk, took us to the Best Chance Mine.

It was quickly apparent on the walk why this area was staked – the green is a sign of copper.

We walked by some very shallow explorations, then came to the main shaft. Judging by the amount of waste rock around it, the 15 feet or so of depth that can be seen now is about as far as they went. There’s water at the bottom but appears to not be deep. A spot above it has a board across it to prevent anyone stumbling into it, but none of the shafts, pits, or other diggings in the Copper Belt are fenced. When you hike in the Copper Belt, you’re on your own.

Back on the road, made a brief stop at the Grafter Mine’s load-out ramp where railway cars got filled with ore. In another of Tim’s history hikes in August 2021, we had a good look at the Grafter property, and saw more of the Best Chance as well.

Although most of the northern part of the railway is now the road, at 2:35 (3½ hours into the tour) we stopped and made another short walk to a short section of original railbed that looped around a rock outcropping that was blasted.

Our next stop didn’t look like much but is historically significant. To quote from Tim’s site, “In winter, water would come down the slope in this area and freeze over the tracks in what crews called a “glacier” (technically an aufeis). This caused derailments in 1910 and 1918. If you look carefully just down the bank to the east, you may find two bits of rail (one badly bent) some other hardware, maybe left over from the derailments.” The derailment in March 1918 killed the engineer and pilot on a White Pass rotary snow plow – read the newspaper article about that tragedy here.

The tour ended with a long walk to visit several railway sites. We parked at the McIntyre Marsh parking area where the Haul Road meets the Fish Lake Road, and walked from there. First, below the road in what is now a marsh, a wye was constructed for turning locomotives around. Next, we visited a memorial cairn – 200 meters north of this cairn, nine miners were trapped in a cave-in at the Pueblo Mine on March 21, 1917. Three were rescued, the other six remain somewhere under your feet as you stand here.

From there we walked past Icy Waters, “one of the premier Arctic charr farms in the world,” then headed into the bush along what would be have the railbed for cars waiting to be filled at the Pueblo Mine.

This was the ugliest bushwhacking of the day, but the site at the end was a must-see. What you see in the next photo is the end of the Copper Mines Branch of the White Pass and Yukon Route railway. Rather than just a wooden or steel bumper as was usual, the rails were ramped up before the bumper that can be presumed to also have been there.

The final site of the day was what Tim called a “bonus” adit (probably from the Pueblo). It only goes in about 15 feet.

That adit was a great place for Tim to get a photo of “the survivors” of this most excellent tour 🙂

From the McIntyre Marsh parking area it’s an easy 26-km drive home. With the “exploration adrenalin” now worn off, when I got home it was all I could do to get out of the car and into the house. If not for the fact that Cathy and the dogs were waiting for me, I probably would have had a nap in the car. Sometimes I think that pushing beyond my abilities ultimately hurts me, but I don’t know that for sure.

I’ve been unable to write blog posts for the last 3 trips/outings I’ve been on, but I’m very pleased to have been able to tell you about this one, perhaps because the story line was clear, unlike the previous three.

Is always my pleasure to find a new posting.. follow some neat links…and more often than not… go BACK in the pages to a similar journey from a different year (your always interesting RELATED POSTS) and finish the coffee or tea. Thanks for sharing and glad that you are still having fun sharing these little adventures with your readers.

Great information, you really do get out and about!

You haven’t lost any of your magical storytelling ability in this fascinating post. Along with the great photography it was a very pleasant and informative way to enjoy my cup of coffee. Even after all those years working at the mine (surveying, line cutting, field geology, assaying, on filters in the mill, underground development, Dostoevsky in spare time in the mine dry) I never knew there was a WPYR rail spur to Fish Lake.