Helicopter to a crashed USAF C-47 north of Haines Junction

A few weeks ago, I got a call from a friend who was trying to get 6 people together to fly to the most iconic of the many plane crashes in the Yukon – a C-47 high on a barren mountain north of Haines Junction. Yes, I was in!

Putting together something like that can be like herding cats, but Gerry put it together. A last minute time change due to other commitments at Trans North Helicopters moved us from 1:30 to 6pm on July 12th, but in the Land of the Midnight Sun, that made no real difference.

I left home at 4:00 for the 169-km drive to the Haines Junction Airport. The weather was quite good, as was the forecast. Nearing Haines Junction, though, the weather reality ahead was much different.

I drove into a wild storm at the airport, with high winds and heavy rain. By 6:10, though it was passing over.

A few minutes later, our magic carpet arrived – a 1994 Bell 206L-4 LongRanger, registration C-GESH.

We met our pilot, Ian, and a quick safety briefing, the 6 passengers were getting buckled in. In the Long Ranger, even the person in the rear middle seat has great viewing.

Away we go, heading north at 6:43. Pretty much as soon as we were airborne, I realized that I should have brought my Garmin Summit to track our route.

From my rear-facing seat, the view was to the east. The large lake is Pine Lake, with the Alaska Highway in the centre of the photo. There were rainstorms in every direction.

A close look at the slopes of Paint Mountain.

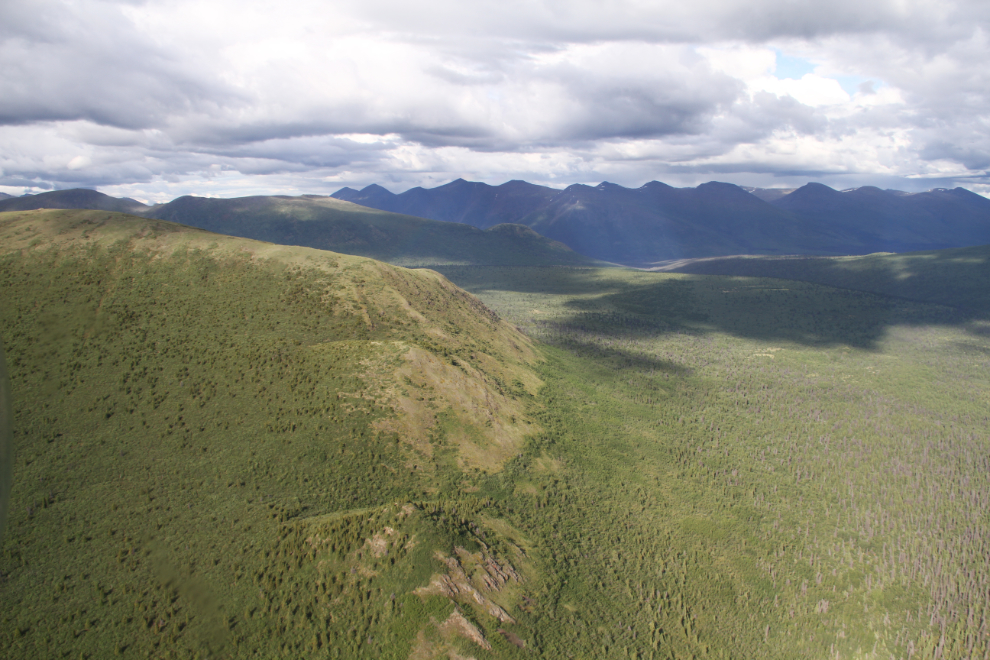

North of Paint Mountain, Ian angled the helicopter off to the northeast. This is vast country, with the odd ATV trail the only sign that humans travel through it.

The valleys have a lot of thick brush, but one you get above that, there are some superb ridges for hiking. Most species of Yukon wildlife live down there – grizzlies, moose, caribou, sheep….

Flying up Marshall Creek at 6:49, we spotted the only cabin along our 100-km route. It’s the tiny green roof above and left of centre in the next photo.

Nearing 7,000 feet elevation, at 6:51. At one point, Ian asked if everyone was feeling okay, because everybody had stopped talking. I guess we were all just stunned by how incredible the Yukon is from the air.

It’s the great, big, broad land ‘way up yonder,

It’s the forests where silence has lease;

It’s the beauty that thrills me with wonder,

It’s the stillness that fills me with peace.

(“The Spell of the Yukon”, Robert W. Service, 1907)

There are 3 Dall sheep rams down there. They were not happy about the noise, but we were gone in just a few seconds.

A couple of minutes before 7:00, Ian settled the helicopter on a saddle of broken rock literally in the middle of nowhere. He said that the C-47 was just ahead and below our position.

Incredible. I controlled my excitement so that everyone could get initial shots of the wreck without any people in them.

The aircraft is a Douglas C-47D, the US military designation for a DC-3. This one crashed on February 7, 1950 while searching for a USAF C-54 troop transport that vanished while flying from Alaska to Montana. There were 44 people on board – 8 crew members and 36 passengers, including 2 civilians, a woman and her infant son. That aircraft has never been found, though people continue the search each summer to this day.

This C-47, U.S. Army Air Force unit number 45-1037, was based at Eielson Air Force Base in Anchorage. The Army Air Forces “Report of Major Accident” says that the accident occurred at 19:45 Zulu, which is 11:45 local time. “Aircraft departed Whitehorse, Canada, at approximately 0815, 7 February 1950 to participate in search for a missing USAF C-54. The crew was assigned a search area 35 to 50 miles south of Ashihik [sic – Aishihik] in the Yukon Territory. Upon arrival at the search area the weather was overcast to broken. Descent to 4000′ indicated was made and search was performed in the east side of the area. A parallel search of surrounding mountain peaks was not made due to low-hanging broken cloud. When the search of the eastern portion of the area had been completed, the aircraft climbed to an altitude of 7500 feet and contacted Whitehorse, giving a position report. A descent was then made to 5000′ and proceeded toward the western portion of the search area. The pass through which the pilot had intended to fly in order to get into the other portion of the area closed in due to ice fog. A turn was made and another pass selected which appeared to have ample clearance. Pilot applied normal climb power-settings and continued toward the saddle-back. A down-draft was encountered which stopped the climb of the aircraft. As soon as the aircraft was clear of the downdraft full power was applied to the engines. Another down-draft was encountered at this time and aircraft flew into the side of the mountain.”

There were 10 people on board the plane, and remarkably, all survived, and injuries were relatively minor. The pilot was 28-year-old First Lieutenant Donald J. King. The rest of the crew consisted of co-pilot Second Lieutenant Homer L. Zachariae, radio operator Master Sergeant Charles R. Dunne, and flight engineers Sergeant Edward J. Wesloski and PFC Richard L. Toth. Also on board were 5 Canadian search spotters, Privates P.R. Sweeney, J.C. Shaw, R.H. Clappison, O.O. Carter, and M. Chimko.

From the next photo on, most of the photos have been processed as HDR images to bring out all the detail.

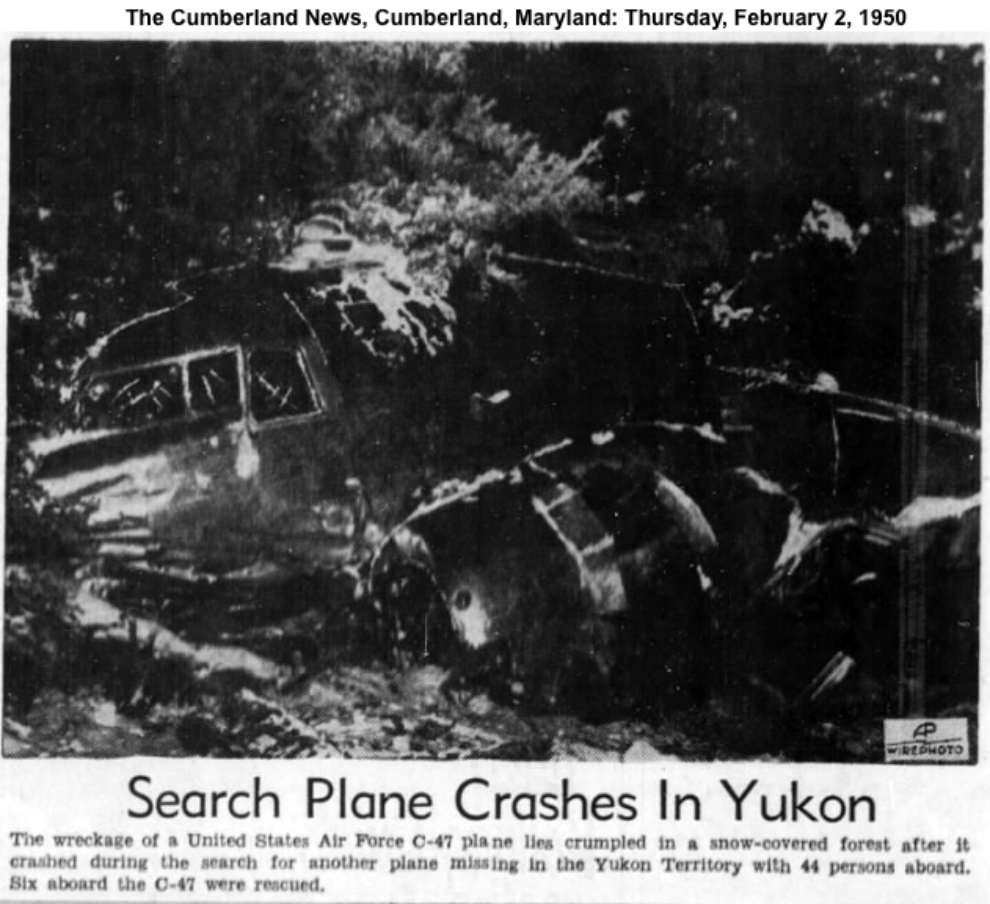

When I began writing this post, it took a few hours to get the real story of the rescue put together. Ian told us that at least one member of the crew had walked to the highway. That would have been an incredible survival story, but it’s not true. The confusion comes in because another C-47 involved in the search had crashed on Mount Lorne south of Whitehorse on February 1st – the pilot of that crash had walked about 5 miles to the Carcross Road. The newspaper photo below is one of many articles about that crash, in newspapers across North America.

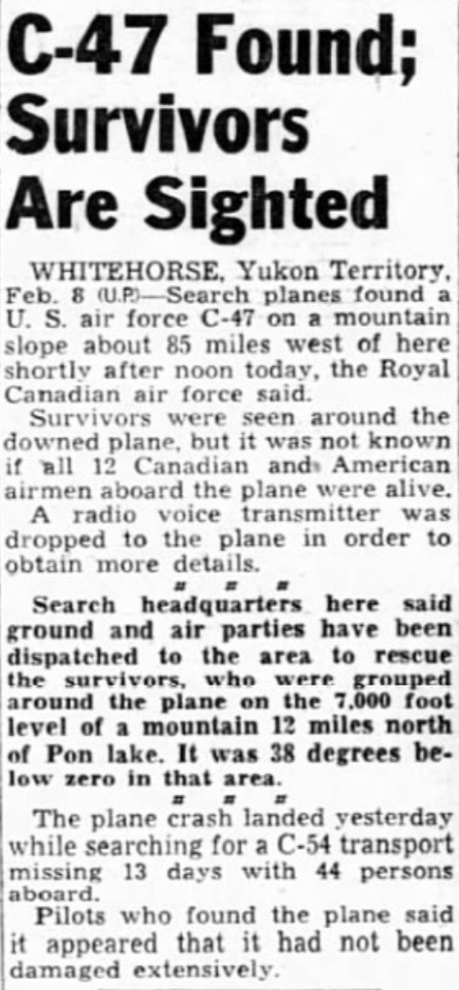

On Wednesday, February 8th, the day after the crash, newspaper articles started to appear. Due to the position report that the pilot had climbed out of the valley to make, and the fact that clear S.O.S. signals were able to be transmitted from the C-47, the crash site had been found fairly quickly. However, both “Aircraft Missing” and “Aircraft Found” articles appeared in various newspapers that day. The article that follows, and many others, use “Pon Lake” as a location reference, but there is no lake officially named that in the Yukon – I’m fairly certain that Pine Lake is the one being referred to. Most of the articles say that 12 men were on board, but there were only 10 according to the official crash report quoted above. Many reports say that the temperature at the crash site was -38°F (that’s -39°C).

On Thursday, February 9th, newspaper reports included statements such as “Ten men, three with painfully broken bones, huddled miserably today in the wreckage of their C-47 search plane which crashed Tuesday on a frozen Yukon mountainside.” The injury reports were soon changed to one man with a broken leg, one with chest injuries, and a third in shock.

Food, sleeping bags, and firewood were dropped to the men at the crash site by the first rescue plane to spot them.

A rescue party was flown to an emergency airstrip which had been built on the ice of Pine Lake, and “slogged over virtually impassable terrain toward the crash site.” The rescue party was soon joined by four M29 Weasels, a tracked vehicle built by Studebaker, which were sent ahead to break trail. One newspaper reported that “The 10-man rescue party consisted of crack U.S. mountain ski troops from Camp Carson, Colo., and Canadian soldiers trained in Arctic rescue work.” and another said that “The veteran 10-man group was equipped with sleds, ropes, and ice axes for shopping out steps in steep, slippery places. The survivors will be placed on the sleds and eased down the peak with the ropes.”

By nightfall on the 9th, the rescue party (minus two of the Weasels which had tracks come off) had reached the valley to the west of the crash site. The men planned to climb the last 2,000 feet of steep mountainside in the morning. In the meantime, though 6 rescue personnel including a doctor had dropped to the C-47 from an RCAF Dakota by parachute (“Dakota” was the Canadian military designation for a C-47/DC-3).

On the afternoon of February 10th, the rescue was completed when a USAF rescue helicopter made 5 trips to the base of the mountain below the crash scene and brought out 9 men. When darkness fell, “The 10th man, Lance-Corporal Mike Chimko, of Kelvington, Sask., remained with a ground rescue party at the base of the peak.” The pilot, Lt. King, told reporters that the slide down the 45-degree slope to the helicopter landing site was the only time during the ordeal that he was frightened: “If a guy couldn’t dig his heels in to stop himself every so often he had a free ticket to hell – he’d drop all the way into the valley.”

The story that Lt. Don King, the pilot, seems to have told reporters is very different that what the official report states. “We were flying through a mountain pass when the weather gummed in on us,” he recalled. “We were caught and just couldn’t get out. Visibility was practically nil. We swerved away from jutting rock and just before we pancaked at the top of the mountain I pulled the stick back.”

The closest brush with death during the crash was that of M/Sgt. Charles Dunne. He had gotten half out of his seat when the aircraft struck the mountain. A propeller broke off and came through the side of the fuselage, breaking his leg. “If I’d still been in my seat it would have killed me.”

This photo of the crash scene was widely published on February 10th and 11th.

So, that was how the C-47 arrived here and the crew left the site. Now, we have this amazing site to visit. The next photo shows the co-pilot’s side of the cockpit.

The condition of the aircraft is remarkable. Covered in snow for most of the year, everything, inside and out, and in exceptionally good condition. Snow and ice driven by winds even keep much of the aluminum polished to a high gloss.

The number on the tail, 51037, is a shortened version of its Army Air Force number, 45-1037.

I mostly just walked slowly around the aircraft, marvelling at the scene. And now having followed the actual story through newspapers of the time, marvelling at the skill, teamwork and heroism that resulted in everyone surviving what could easily have been an unsurvivable crash.

The interior looks much the same as it did once the air force parts-removal team finished with it 67 years ago.

The position of this damage at the outboard edge of the engine means that it was the landing gear that caused it.

After about 20 minutes at the crash site, a cloud started to blanket the slope, and it was time to get back to the helicopter. I wasn’t “finished” yet, but I had documented the site to my satisfaction. Now I just wanted to sit back and look at the plane and the mountains and think about the events that led to it being here.

Walking back to the helicopter. The iconic C-47 vanishes into the mist.

I stopped just long enough to lay down to capture a bit of colour in this now gray world.

Well that’s not good! With a helicopter, it’s possible to fly with that much visibility (low and slow!), but it’s certainly not recommended.

Within a few minutes, the cloud had blown over, and we lifted off the mountain at 7:38. Two minutes later, we passed over this small, still-frozen lake.

As much as I’m tired of the weather we get in the Yukon, outings like this confirm the fact that I can never leave this country. Most Yukoners who have left say that while you may leave the Yukon, the Yukon never leaves you.

At 7:46, just 8 minutes after leaving the crash site, the Alaska Highway could be seen in the distance.

Back over the Haines Junction airport at 7:49.

It took a few minutes for Ian to get his bird tied down for the night, and then we went back to the office to pay for the trip. The cost broke down to $135.60 per person. Everybody agreed that it was an absolutely incredible experience for that sort of money.

One last look at “Echo Sierra Hotel” and we were all on our way back to Whitehorse.

Just a few miles from the airport, the skies opened up in a major way! That would have been nasty up on the mountain.

Looking south (east actually) right at Km 1474 of the Alaska Highway, at 9:14 pm. What a crazy weather-day.

One final shot from the day, of part of the 8 km of Alaska Highway that’s being re-constructed to get rid of some really bad heaves that have been getting worse and worse for 20 years or so.