By skiplane to Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak

Many years ago, Cathy was in the right place at the right time, and flew to Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak at 5,959 meters high (19,551 feet). It’s also the largest non-volcanic mountain in the world in terms of mass – it’s 100 miles around the base. Last Monday (August 1st), she and I finally got to experience the flight and glacier landing that Icefield Discovery calls “The Ultimate Experience!” – and we now definitely agree with that name.

We’ve driven down this road to Icefield Discovery’s base on Kluane Lake a few times, but things have never worked out before, usually because of the weather in the back country. As recently as 3 weeks ago, we drove in and made a reservation for the next day, but then the weather shut down. Their base is located at the Silver City airport, where the Arctic Institute of North America’s Kluane Lake Research Station is also located. Last year, the Yukon News published an excellent story about Icefield Discovery’s history.

This is the office of the Chief Pilot, Tom Bradley – the main office is on the other side of the runway.

C-GXFB, a 1966 Helio H-295-1200 Super Courier on retractable skis, would be our chariot to the ice. This incredible aircraft, with twin turbochargers on a 295-hp Lycoming engine, can take off and land at 30 mph on gravel/dirt strips less than 500 feet long, and can climb to over 20,000 feet.

I asked for the front seat and all of the 3 women flying agreed. Having a few hundred hours in the left seat of little planes, I love seeing the various components of “the office” at work.

At 4:05 pm, we started taxiing to the far end of the gravel runway, and at 4:13, our takeoff would have looked like this (this is a photo of a takeoff the next day). The elevation of the airport is 783 meters (2,570 feet).

A minute later, we were looking down on the Slims River pouring silt into Kluane Lake, with Sheep Mountain towering over them. The furthest, whitest beach is the one we’ve been playing with Bella and Tucker on recently.

The old Alaska Highway leads from the new highway out of sight to the right, to the parking lot in the centre of the photo. From there, you can hike the Slims River West, Sheep Creek, and Bullion Creek trails.

Sheep Creek.

Bullion Creek.

Looking south, up the Slims River towards the Kaskawulsh Glacier.

One of the many impressive deltas along the Slims River valley. I’m still reading scientific literature to confirm a few things, but these seem to me to be kame deltas, formed when the creeks emptied their sediment into the lake that existed here as the Kaskawulsh Glacier started retreating some 12,000 years ago. We were now climbing through 6,700 feet (I took several photos of the altimeter to keep track of this).

To the right of centre is a large rock glacier along Canada Creek. A rock glacier can be either a mixture of rock and ice, or ice overlain by rock and gravels. This is one of many in the area. Along the Haines Highway, the Rock Glacier Trail is a popular hike.

There are glaciers everywhere – most of them, as with most of the mountains, are unnamed. I think that Tom told us the name of this one, but it’s not on any of my maps.

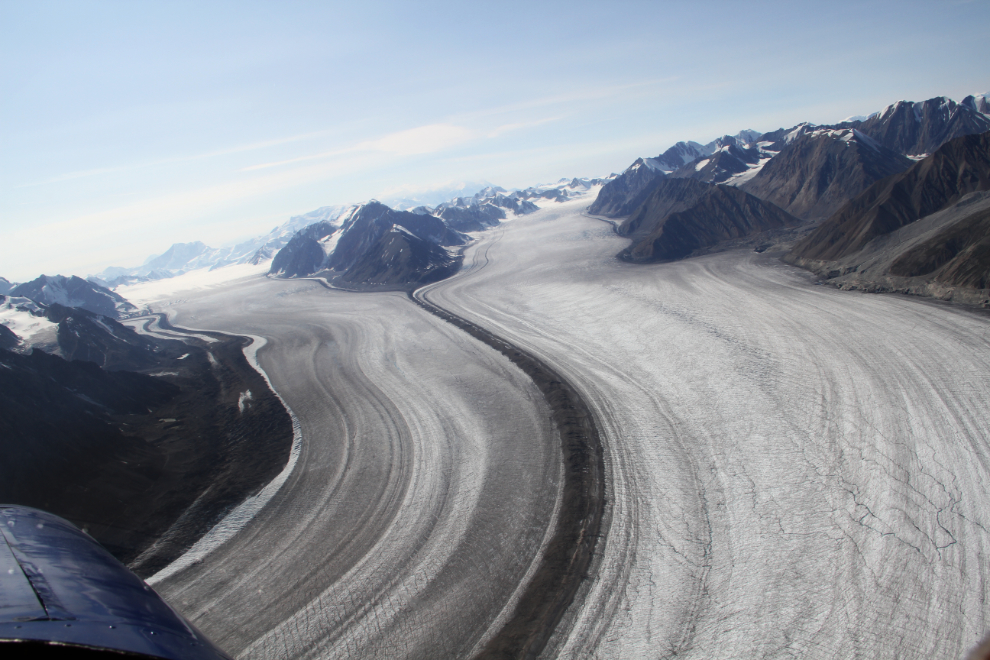

The size of the Kaskawulsh Glacier is stunning, with a surface area of more than 25,000 square kilometers (15,000 square miles).

The Central Arm to the left is about 3.5 km wide, and the North Arm is about 2 km wide. Where the two arms converge to form the Kaskawulsh Glacier, the width is 5-6 km.

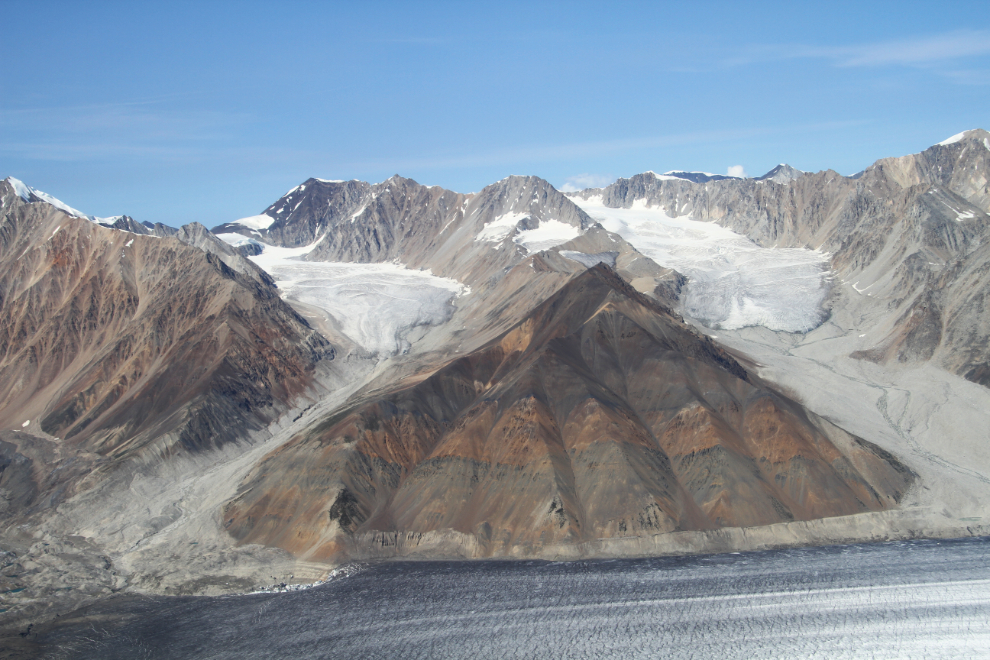

It’s hard to imagine the volume of ice that’s been lost since the days when these two glaciers met the North Arm, or the volume that’s been lost by the North Arm as evidenced by the ice scars on the slopes above it.

Up in the land of permanent snow, flying at about 8,600 feet, the surface of the glacier smooths out a lot, but there are lots of massive caves, snow bridges, and pools of the most amazing blue water. Many glaciers flow from these high-altitude Kluane icefields, the largest non-polar icefields in the world.

Our destination, the Icefield Discovery Base Camp. This heated 16×32-foot hut houses washing, cooking and dining facilities for vistors who want to learn about glaciers while living on one for 3 days.

On the Hubbard Glacier, at 60° 41.00N, 139° 47.13W, at 2,607 meters (8,553 feet) elevation.

Tom Bradley with Cathy.

Me and Cathy.

The north-east face of Mount Logan and our ski tracks.

Tom kept the engine of the plane running for the half-hour that we were on the glacier – that’s not the place to have a dead battery or any other engine issue.

In this vast world of rock and ice, the 5 of us in the plane were probably the only people. It’s a very different feeling than flying at Denali, where you know that there are always lots of other people experiencing it.

Avalanches happen constantly on these very steep mountains, which are still growing due to tectonic plate activity.

On the climb up to Icefield Discovery Base Camp, we had been high over the Kaskawulsh Glacier, but on the return flight, Tom gave us a much closer look. The medial moraine formed when the North and Central Arms converge is much higher than I thought. From a lower altitude it was obvious how difficult travel across the glacier would be in the summer.

There really are no words to properly describe this world, and the closer look makes that even more true. The wreckage of a Cessna 180 that crashed many years ago can still be seen on the glacier.

The variety of colours was quite surprising to me, from the green on some of the slopes to the different colours of rock and gravels in the moraines, speckled with blue water in streams and pools.

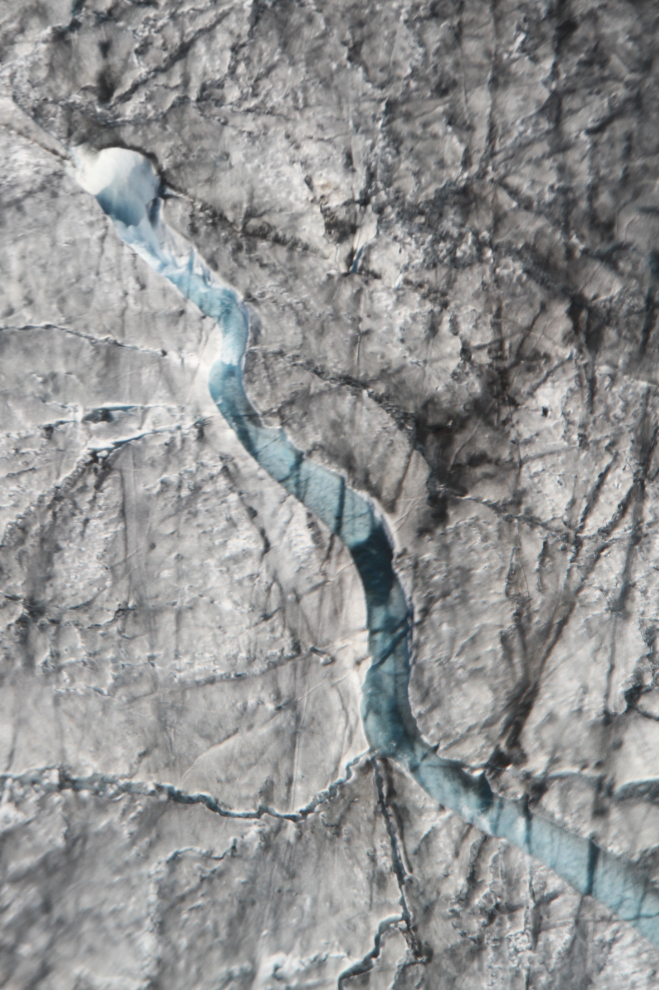

In the centre of this photo, a stream running across the top of the Kaskawulsh Glacier drops into a moulin – they can be extremely deep, possibly right to the bottom of the glacier, which at this point is about 500 meters thick (1,640 feet). It’s hard to judge scale, but I’d guess this moulin to be about 10 feet across.

By the time you get near the toe of the glacier, there’s more gravel visible than ice. From the end of the Slims River West Trail, hikers can climb Observation Mountain, just to the left of the ridge seen in this photo, for incredible views of the Kaskawulsh Glacier.

The Kaskawulsh Glacier has drained into two rivers, the Slims and Alsek, for many years, but the channel marked by the arrow is new as of this Spring, and now virtually all the glacier’s outflow goes into the Alsek system. This has resulted in a lowering of the level of Kluane Lake by 10-12 feet.

The vast Slims River valley is now nearly dry in its upper reaches, and dust storms are getting more common and more impressive.

The huge alluvial fan (or perhaps a kame delta) of Vulcan Creek. In September 2014, a landslide near the headwaters of Vulcan Creek created a new lake.

Passing over the ghost town of Silver City (a.k.a Kluane). Although privately owned, there are no controls on use, and it’s fairly heavily visited.

This is the mouth of Silver Creek, which is heavily controlled for a mile or so as it passes under the Alaska Highway. The lack of a regular channel that you see here has done a lot of damage over the years, including to the Silver City ghost town. This is known as a “braided river” and is typical of glacial rivers.

On final approach to Silver City at 5:45.

While the creations of Mother Nature were the main star of this experience, our pilot, Tom Bradley, added immensely to it. His passion for mountain and glacier flying is wonderful to share, and his virtually non-stop sharing of his deep knowledge of the area places this flight as the best that Cathy or I have ever made. We’re already talking to him about a longer charter for next season, to fly right around Mount Logan.