A Yukon natural history day

I spent Friday at a Natural History and Nature Interpretation workshop. Offered to Yukon guides by the Wilderness Tourism Association of the Yukon, its purpose was to increase the level of knowledge of people who already have a solid base and to help them interpret the Yukon’s wildlife and wild spaces to their clients. There were a wide range of participants, from 20-somethings to 60-somethings, with both cheechakos and sourdoughs in the mix. As well as what I do online, I’ll be a guiding at least one tour for Ruby Range Adventure this summer, an 11-day one from Whitehorse to Seward for a group from New Zealand.

We met at McIntyre Marsh at 09:00 am. I wonder how many Whitehorse residents have ever been up Fish Lake Road? My guess is that it’s a low number, but it takes days to have even a quick look at some of the great locations up there – McIntyre Marsh, Haeckel Hill, Fish Lake and Mt. McIntyre being the main attractions.

The photo below shows an overview of McIntyre Marsh. Although the terms marsh, swamp and bog are often used interchangeably, the Canadian Encyclopedia gives good basic descriptions that show how a marsh is different. The introduction says:

Marshes are treeless wetland where lush growths of herbaceous plants (eg, grasses, sedges, reeds and cattails) predominate. Marshes usually form in quiet shallows of ponds, lakes and rivers, and along sheltered coastlines where mineral nutrients are available. They are highly productive ecosystems teeming with life.

The workshop leaders were Andrea Altherr (on the left) and Dave Mossop. Andrea is a guide herself, while Dave is a biologist with a wide-raging knowledge and a particular passion for birds.

Our first stop was at the bird banding station. Each of those bags holds a bird that’s just been brought in from the mist nets that were set up in late April.

I found it fascinating to watch Ted banding tiny birds such as this Common Yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas). It only weighs about 1/3 of an ounce (10 grams) and he made it look so easy, but it must take a great deal of practise.

I love birds but my frustration in not being to identify a bird’s species even with all the books I have (Sibley’s being the best by far) stops me from being a serious “birder”. This is a sparrow, but I don’t know which one.

We went for a long walk along a ridge above the marsh. This was our primary location for seeing and discussing what we saw – the trees, the smaller plants, the birds and the mammals. As the encyclopedia says, this is a “highly productive ecosystem teeming with life.” An example of the sort of upgrading of our interpreations that this workshop targetted: although we may use the term “grasses” for the most obvious plant in the marsh, they aren’t grasses, they’re sedges (among other differences, grasses have round stalks, sedges have edges).

A bald eagle feather that was found along the trail ended up in Dave’s hat after a discussion about how to identify its source 🙂

The Trans Canada Trail that runs across the marsh is popular year-round, for cross-country skis, snowmobiles and dogsleds (note the sign “Power Yields for Paws” – dogsleds have priority) in the winter, mountain bikes and all manner of vehicles in the summer. The trail was once a copper-mining haul road.

We took a lunch break and then headed out to the Yukon Wildlife Preserve for the afternoon. It’s located near Takhini Hot Springs, about a 20 minute drive from McIntyre Marsh.

The welcome centre. Although bus tours are available, our group opted for the 5 km walking route. This 700-acre facility was developed as a private game farm by Danny and Uli Nowlan and when they retired, it was purchased by the Yukon government. It re-opened in its current form in the Spring of 2004.

The first birdhouse we came to was being used by Mountain Bluebirds (Sialia currocoides), who had built their nest from qiviut shed from the preserve’s muskoxen – certainly the most luxurious nesting material possible (it’s softer than cashmere and much more expensive).

Right beind the welcome centre are some elk (Cervus canadensis).

This Dall Sheep (Ovis dalli dalli) is a member of the most common sheep species in the Yukon, easily identifiable by being all white. This fellow was extremely sociable!

Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) are becoming more and more common in the Yukon, but may be threatened by the very aggressive Whitetails that have started to move in. The central Yukon is the furthest-north part of their range.

A male Northern Shoveler (Anas clypeata) in the wetlands in the centre of the preserve.

This Red-necked Phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus) was nearby. One of the things that was reinforced during this workshop was that despite my efforts to make my property bird-friendly, I also do things that are very bird-unfriendly. I heat my home with wood, which reduces the number of dead trees that so many species use to nest, and I have a “mosquito magnet” machine that greatly reduces the birds’ primary food source (but also makes my property more enjoyable for us).

Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) are fascinating creatures – their ability to survive in some of the toughest climates on earth is amazing. They look a bit like bison (buffalo) and for that reason most people are very surprised by how small they are.

Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) are well know for their curiosity, and that curiosity lends itself well to this educational environment. This female seemed to be as interested in us as we were in her.

The unique hoof and ankle structure of the caribou, as well as allowing them to walk on soft ground and dig through snow for food, makes a clicking sound as they walk.

All 3 of the Canada Lynx (Lynx canadensis) were off in shady spots out of the hot sun (well, hot for us – it hit 24°C, 75°F). They’re much more active in the winter.

The Arctic foxes (Alopex lagopus) are just beginning to change to their summer grey colour.

The Mountain Goats (Oreamnos americanus) tend to keep their distance from the road that passes by their cliff habitat.

Population control is a major issue that the preserve is dealing with, and the only baby mountain goats we saw this year were on the interpretive sign.

The Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae) were in ashadt forest when we went by their enclosure the first time but were out in the sun as we neared the end of our walk. Weighing about a ton, this bull is a good example of the species that is the largest mammal in North America.

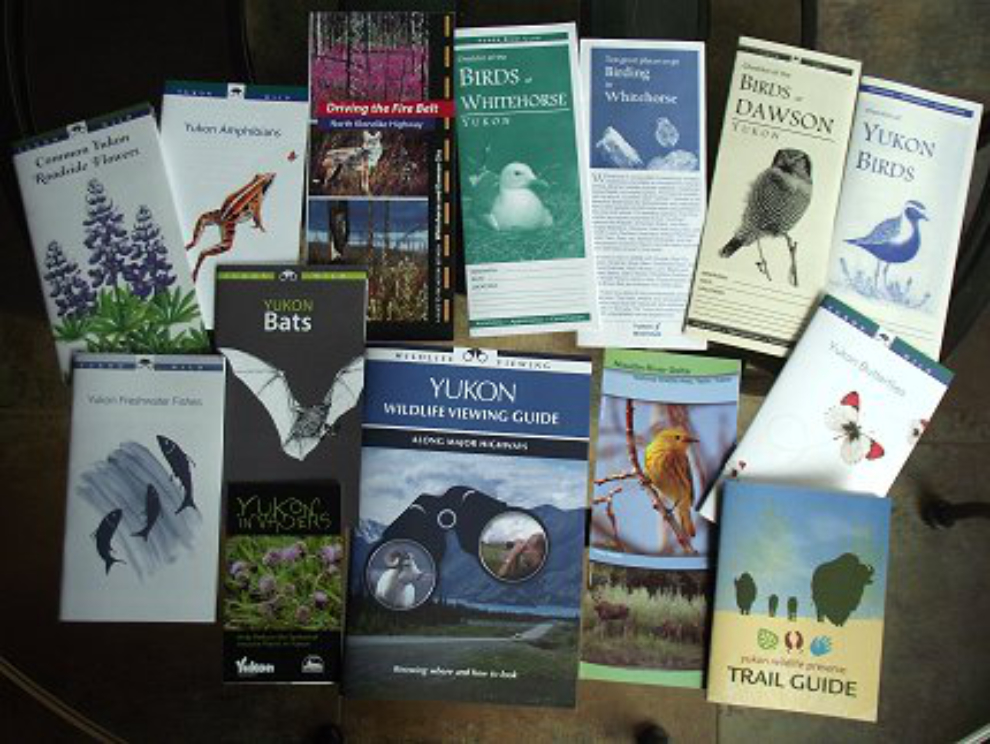

The workshop ended just after 4:00 pm. It had been an extremely productive day, and I came away feeling that it had accomplished its purpose. This last photo shows the brochures that I picked up, some of the ones available at the Environment Yukon Web site, at their office on Burns Road in Whitehorse and at Visitor Reception Centres around the territory.